Before March 2020, the Canadian public probably would have rebelled at the idea of a program that delivered a full-time minimum wage to 20% of the population without requiring them to demonstrate that they couldn’t find a job. A global pandemic has created an ideological shift where many of us are suddenly very empathetic with the unemployed — and this gives Canada an opportunity to trial unprecedented policies and ask some never-before-possible questions, including: what happens when we just give people money?

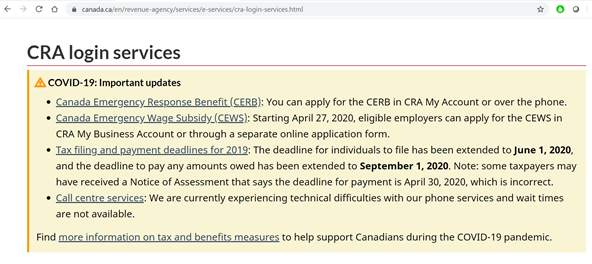

The Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) was introduced in March 2020 to provide urgent relief to Canadians due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike the country’s long-standing Employment Insurance (EI) program, the CERB includes self-employed, freelance, and gig economy workers, as well as people who have lost work due to illness or any coronavirus-related reason other than “quitting voluntarily.”[i] The CERB has been heralded for being easy to access,[ii] unlike many other wage subsidy or replacement programs — currently, the CERB is advertised across bright banners in most of the locations Canadians go online to file their taxes.

Screenshot from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) portal for individual login services, April 2020

While Canadian pundits are divided on whether the CERB has hit the ideal parameters for who qualifies to receive it,[iii] some have begun to compare the program to an idea with a long and controversial history: Basic Income or Universal Basic Income (UBI), which are related, but not synonymous, terms.[iv] The CERB is like a UBI in two main ways that will be highlighted in this post: first, it is much closer to “universality” than most other programs of its kind in the number of Canadians who qualify for it; and second, it is substantial enough to be considered a meaningful replacement for “income.” Canada has several cash-transfer programs — notably, EI and the Canada Child Benefit (CCB) — but these programs are typically some combination of means-tested, below-income replacement, conditional on job seeking, etc. and thus lack CERB’s similarities to basic income.[v] Canada is not alone in implementing something like a basic income in light of the coronavirus problem. Numerous countries have implemented cash-transfer policies, and Spain, notably, has begun to talk of instituting a policy that would last beyond the current crisis.

These policy measures are coming at a very unique time — indeed, the economy is all but shut down due to social distancing — and as such, measuring the outcomes of social programs like the CERB will be both very difficult and an unprecedented opportunity. Accordingly, this post doesn’t seek to weigh in on whether or not the CERB is the best policy response for this emergency, but rather explores some of the most important research questions Canadian institutions can ask while this measure is in place. In what follows, I’ll talk about what UBI is, why it’s an important concept for understanding the CERB and the alternate program of EI, and how international scholarship has long been analyzing cash-transfer programs and their outcomes around the world.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

What is Universal Basic Income?

The idea of UBI was recently popularized in North America by American Presidential hopeful Andrew Yang (rebranded as the Freedom Dividend) but the concept has a long history, originating with early utopian thinkers such as Thomas More and Thomas Paine.[vi] Basic income entails providing a guaranteed sum (usually monthly) sufficient for a baseline standard of living. Universal (U)BI means that the sum goes to every individual in a jurisdiction. There are also several variations on this concept, including negative income tax measures and targeted basic income, which offer alternate policy approaches.

As mentioned, the CERB shares several characteristics with UBI. First, it is closer than any previous program to UBI “universality.” The Government of Canada has already begun to track CERB data. A dashboard with the most important figures is currently available here and shows that to date (Apr. 28, 2020) 7.28M unique individuals have applied for the CERB — a staggering 19.2% of the Canadian population,[vii] about 1 in 5 Canadians. The CERB is available to anyone whose employment has been negatively impacted by the coronavirus, and it does not rely on previous income, existing assets, or employment-seeking behaviours for qualification.

Universal and Unconditional — the Controversial Bit

Why give money to the rich as well as the vulnerable? This is a common argument raised against the basic proposal of UBI, whose proponents contend that removing “means-testing” (the process of testing applicants’ level of income or support to determine if they are eligible for a program) is essential to implementing real income replacement.[viii] From a UBI advocate’s perspective, means-testing has several negative consequences.

For example, means-testing…

… may perpetuate stigmas around EI and similar programs (if a program is only for “the poor,” there may be shame attached to it that prevents people from applying).

… means that the program will not reach some of the most vulnerable. The moment that “applying” becomes part of a social program, certain people in the target population are lost due to lack of access or lack of knowledge. For example, only about 36% of unemployed persons in Canada were receiving EI benefits in January 2019.[ix]

… often writes a vulnerable population out of the policy (in the case of EI, many people who are self-employed or in the gig economy) due to the difficulty of establishing ideal eligibility criteria and including everyone who needs the program.

In addition, some proponents argue that means-testing perpetuates a hefty bureaucracy, the funds of which should go directly to the population. It is because of this last argument that UBI is sometimes characterized as a libertarian, “anti-big government” ideology — and indeed, its supporters fall on both sides of the political spectrum.

Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

“Basic Income” or Income Replacement — the Other Controversial Bit

A second fundamentally controversial component of UBI is that it is typically intended to be sizeable enough to replace income. For example, the CERB’s $2000.00 monthly payment equals $12.50 an hour full time: higher than the minimum wage in Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland & Labrador, and Saskatchewan. In comparison, other well-known cash-transfer programs, such as South Africa’s widespread Child Support Grants (440 ZAR per dependent per month prior to COVID, to over 20% of the South African population[x]) or the Alaska Permanent Fund (which pays about USD $2000 a year) only provide about $33 CAD and $232 CAD monthly, respectively. Accordingly, these are often characterized as widespread cash transfers that hint at, but do not quite comply with, the parameters of basic income.

The arguments for income-replacement-level funds vary. Some (often out of Silicon Valley and the tech sector, including the line taken by Andrew Yang’s campaign) suggest that with greater automation, society will begin producing more wealth than meaningful jobs, and that it might be better to tax that wealth (see ideas such as Bill Gates’ robot tax) and redistribute it than contrive new occupations. Some arguments, often from the academic world, seek instead to question the value placed on labour force participation as a measure of social contribution.[xi] Many in both camps also argue that income-level replacement will pay for itself via improved health outcomes,[xii] decreased crime,[xiii] or other social benefits.

The arguments against UBI are also numerous: that social income should be reserved only for the vulnerable, that it disincentivizes workplace participation, that workplace participation is more important than UBI advocates might attest, and that automation is unlikely to occur soon. Finally, many simply argue that UBI would be economically infeasible — like the question of public or private healthcare, this varies depending on the variables and models that economists use to predict UBI’s economic impact (see for example The Roosevelt Institute: UBI will grow the economy vs. University of Pennsylvania: UBI will shrink hours worked, capital services, GDP, and Social Security).

The Jury Is Out on UBI, so What’s Valuable About Using It As a Framework?

You guessed it: a large and growing collection of pilot studies and research. The public fervour and controversy that UBI stirs up has produced, among numerous op-eds, a set of very useful research questions and principles that can be applied to the CERB as we examine the impact it has had on Canada. Furthermore, many of these same pilot studies have suffered from limiting parameters, such as small budgets for the experiments resulting in too-small population sizes or lower-than-advised monthly payments.[xiv] Canada’s current policy does not have these same issues.

Again, while CERB is not synonymous with UBI for a number of reasons — not least that it is a short-term policy designed to respond to an emergency, rather than a long-term policy designed to improve social outcomes over many years — it may be the closest we come as a country to implementing a universal, nationwide, income-replacement-level cash-transfer program. Taking the lead from numerous Basic Income-related works (see references & further reading), some of the questions that can be asked of Canada and Canadians during this time include:

- What populations are included in or excluded from the CERB? When the dust settles, what vulnerable communities were unable to access it? Why? How can those barriers to access be overcome in the future?

- What were the policy’s goals, and were these met? (E.g., due to pandemic closures and the difficulties of workforce re-entry, how did this policy’s goals differ from those of EI, the CCB, or other programs?)

- What impact did the CERB have on workforce participation during and after COVID-19 (even if it’s not possible to disaggregate from the effects of the virus), including job seeking; career changes; layoffs; entrepreneurship and innovation; and self employment & gig economy participation?

- How are we sustaining the CERB financially? What economic outcomes will this have? What might the economic outcomes have been without the CERB?

- How do people on the CERB spend their time? What activities other than workforce participation are being undertaken?

- How has the CERB impacted consumer spending? In what countries are consumers spending? What impact has the virus had on e-commerce, and what impact has this had on Canadian tax revenues?

- What outcomes do CERB recipients experience related to health; housing status; education; the aforementioned labour market participation & entrepreneurship; and financial status (e.g., debt)? How do these outcomes differ for people such as: Individuals who undertake additional care work or have dependents; formerly self-employed or gig economy individuals; individuals by gender; individuals with very high or very low household incomes prior to the CERB; individuals who identify as Indigenous; individuals in rural or Northern Canada; or newcomers?

- How do the outcomes of Canada’s policy compare with those of other countries, such as Spain?

Beyond suggesting research questions, studies of the world’s cash-transfer programs have, and will continue, to provide Canada with very valuable comparative case studies. In fact, the literature isn’t entirely international: see, for example, the findings from a study held in Dauphin, Manitoba, in the 1970s.[xv] For an overview of some of the work that has already been done to track the effectiveness and feasibility of basic income or cash-transfer programs around the world, take a look at the further reading list below.

References & Further Reading

[i] Government of Canada. “Apply for Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) with CRA.” Last modified 2020, 04, 21. https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/benefits/apply-for-cerb-with-cra.html

[ii] Vanmala Subramaniam. “‘So easy I thought it was fake’: CRA’s CERB system gets stellar reviews in first days of operation.” National Post, April 8, 2020. https://nationalpost.com/news/economy/so-easy-i-thought-it-was-fake-cras-cerb-system-gets-stellar-reviews-in-first-days-of-operation/wcm/64f4bf51-2e2b-4e4a-af98-44364365a213?video_autoplay=true

[iii] Michael Lewis. “One third of Canadian workers won’t be able to access government aid, economist says.” The Toronto Star, April 2, 2020. https://www.thestar.com/business/2020/04/02/covid-19-job-loss-fund-will-let-many-down-analysis-finds.html

[iv] Evelyn Forget & Hugh Segal. “Cerb is an unintended experiment in basic income.” The Globe and Mail. April 19, 2020. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-cerb-is-an-unintended-experiment-in-basic-income/

[v] The Canada Child Benefit, for example, is a simple and wide-reaching program but differs from the CERB both with regard to means testing and with regard to payment sum. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/campaigns/canada-child-benefit.html

[vi] “History of Basic Income.” Basic Income Earth Network. https://basicincome.org/basic-income/history/

[vii] Based on Statistics Canada’s Q1 2020 Population estimate, 37,894,799. Table: 17–10–0009–01, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901.

[viii] “About Basic Income.” Basic Income Earth Network. https://basicincome.org/basic-income/

[ix] Statistics Canada put the country’s total unemployed at 1,218,600 in January 2019 [Table: 14–10–0058–01 (formerly CANSIM 282–0049)] while 435,600 were receiving EI benefits, only about 36% of all unemployed persons.

[x] From an ILO report published in 2015, based on 2014 population & CSG figures. See Sophie Plagerson and Marianne S. Ulriksen. “Cash transfer programmes, poverty reduction and empowerment of women in South Africa.” International Labour Office Working Paper №4 / 2015. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—gender/documents/publication/wcms_428635.pdf, p. 4.

[xi] See for example: James A. Chamberlain. Undoing Work, Rethinking Community: A Critique of the Social Function of Work. ILR Press, 2018.

[xii] See, for example, Evelyn L. Forget’s work on the “Mincome” experiment (note 13).

[xiii] See, for example: Richard Dorsett. “Basic Income as a Policy Lever: Can UBI Reduce Crime?” ProMarket, June 13, 2019. https://promarket.org/basic-income-ubi-reduce-crime%E2%80%A8/

[xiv] Aria Bendix. “One of the world’s largest basic-income trials, a 2-year program in Finland, was a major flop. But experts say the test was flawed.” Business Insider, Dec 8 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/finland-basic-income-experiment-reasons-for-failure-2019-12

[xv] The “Mincome” experiment is chronicled by several sources, including the CBC and multiple academic papers. See for example, Evelyn L. Forget. “The Town with No Poverty: The Health Effects of a Canadian Guaranteed Annual Income Field Experiment.” Canadian Public Policy 37 (3), 2011: p.283–305. https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/full/10.3138/cpp.37.3.283

Additional further reading:

Isabel Ortiz, Christina Behrendt, Andrés Acuña-Ulate, Quynh Anh Nguyen. Universal Basic Income proposals in light of ILO standards: Key issues and global costing. The International Labour Organization (ILO), 2018.

James Ferguson. Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2015.