Following the worst of the COVID-19 lockdowns and layoffs in Canada, the pandemic’s labour market impacts disproportionately fell upon particular communities, including Indigenous, Black, and racialized workers. In January 2022, the Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC), with support from the Walmart Foundation, launched a project that would inform a set of labour market tools and information to support job seekers and career transitioners, particularly those identifying as Indigenous, Black, or racialized. In addition to supporting individual autonomy in career planning, this project seeks to identify and address structural barriers to advancement and career transition and offer practical solutions.

This study builds on existing research that identifies widening gaps in the labour market during COVID by focusing on experiences of career reinvention and advancement, identifying resources for a more diverse workplace that can support access to career planning, and highlighting opportunities for employers and other relevant parties (workforce development organizations, policymakers, etc.) to improve workplace diversity.

This brief summarizes early findings from the study, which will be released in early 2024. We encourage interested parties to get in touch with the research team if they would like to participate or learn more.

What Questions Does this Research Ask, and How Does It Seek to Answer Them?

Figure 1: Central Research Objectives and Questions, ICTC, from the first Equitable Rebound project advisory committee meeting. While the study originally focused only on the experiences of Black and Indigenous job seekers, other racialized persons (and the intersecting experiences of newcomers) have been involved in the project because of input from community-serving organizations who wanted to involve larger cohorts of their clients in primary research.

There are two halves to the Equitable Rebound project. One stream of the research focuses on Canadian employers: it examines the demand for talent across Canada, with a focus on roles that foster improved job mobility and career advancement (e.g., involving transferable skills or a platform for promotion). It also aims to understand and improve strategies for ensuring workplace equity in advancement and mobility. To characterize demand and employer-side strategies for enhancing equity, ICTC has conducted a national employer survey; developed and implemented a national job scraping and aggregation strategy; and conducted key informant interviews with employers, human resources professionals, and subject matter experts.

The second stream of the research focuses on learning from the experiences of Black, Indigenous, and racialized workers and job seekers following the COVID-19 pandemic. Through extensive primary research, this stream seeks to understand the barriers to advancement and transition that people have encountered, what policies and programs have been most helpful in helping them overcome these barriers, and enabling infrastructure that can further support Black, Indigenous, and racialized leadership in this space. Eventually, this project will also seek to produce labour market data and resources that job seekers can use to improve access to career mobility and advancement: part of the research process investigates user experiences with ICTC’s career planning tools and how they can be improved.

So far ICTC has:

- Convened a project advisory committee of 11 subject matter experts to steer the study’s launch and methodology

- Held engagement sessions or conducted in-person interviews in 12 cities across Canada in partnership with community-serving organizations and spoke with 245 workers or job seekers

- Conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 34 community organizations, workforce development professionals, equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) professionals, and other subject matter experts

- Conducted a national employer survey (n = 503) to understand employer strategies for equitable hiring and promotion, workplace safety, and other topics

- Collected information on thousands of jobs and skills that are in demand across Canada through a job scraping and aggregation strategy to produce helpful labour market information for job seekers and career transitioners

Why Focus on Equitable Career Advancement and Transition or Reinvention?

Many other research organizations have done important work revealing significant barriers to labour force participation, equitable pay, and access to specific sectors for Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities in Canada. Notably, a research series by Sheila Block and Grace-Edward Galabuzi examined labour market disparity and recovery and identified continued inequity in employment and salary for Black and racialized men and women following the COVID-19 pandemic, despite a tight labour market and rising wages overall. In their most recent study, Block and Galabuzi conclude that “a rising tide does not lift all boats. Clearly, further policy interventions are needed to address the continued gaps in labour market outcomes for much of the racialized labour force, and for Black workers, in particular.” Similarly, work led by the First Nations Technology Council supported by ICTC in British Columbia identified a persistent dearth of Indigenous people in well-paying roles in the technology sector, driven by “broad systemic barriers to Indigenous access to and participation in tech employment and education.” This report highlighted the importance of supporting Indigenous advancement and leadership in the technology sector and in technology education to improve systemic barriers in workplaces and schools with insightful lived experience.

This study takes its lead from existing work by focusing on strategies for supporting the advancement of Black, Indigenous, and racialized workers in organizations across Canada rather than re-interrogating known inequities in employment and salary.

Career transition or reinvention has been in the news for the last few years for several reasons: colloquially, the “great resignation” (primarily a phenomenon in the United States, with echoes in Canada) identifies a trend where workers are more likely to be ready to leave their jobs or careers for something new. Furthermore, in Canada, some workers who experienced layoffs also received the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) or other support and were able to take stock of their careers and transition to something more secure than front-line, public-facing work.

Accordingly, this study asks, are all workers equally confident in their ability to reinvent their careers in the face of external pressure? And were programs like CERB accessed equitably across Canada? These questions are highly relevant in that if Black, Indigenous, and racialized workers are less free to reinvent their careers, it may tie into continued underrepresentation in well-paying sectors like technology. Furthermore, research suggests that Black and Indigenous workers in Canada are disproportionately present in roles at risk of automation. Career transition, mobility, or reinvention are essential to weathering a quickly changing labour market.

Through these research questions, ICTC has sought to prioritize topics that community-serving organizations identify as primary concerns. Many of the early themes from the research presented in this brief are topics that non-profits, NGOs, and workforce and settlement service providers have reported.

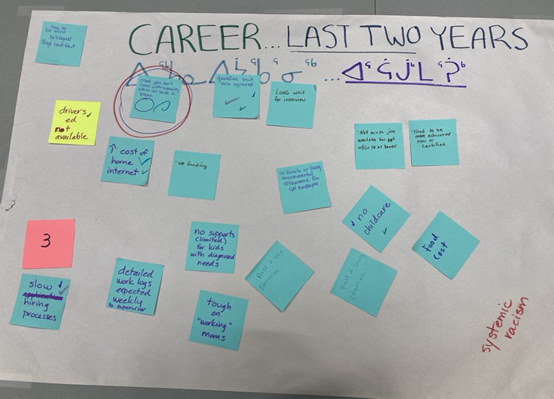

Figure 2: Edmonton, AB, Community Engagement Session, Stanley A. Milner Library, June 2022

Early Themes from the Research

Employers, Equity in the Workplace, and Talent Demand

As discussed above, this project has two main, complementary streams of research. The first focuses on understanding employment demand in Canada and employer strategies to support equitable advancement. The final report will include a breakdown of talent demand in the Canadian economy following COVID-19. This research-in-progress brief will examine early findings on workplace safety and equity.

Many employers declared an intent to improve inclusive hiring during and after COVID-19. EDI experts caution that intent must be coupled with intentional and self-aware workplace strategies.

Many organizations felt moved to make changes to their workforces, boards, and leadership in response to events that occurred during the pandemic. Interviewees for this study who work in Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) consulting or implementation have noted a big change in how organizations view their role in fostering a fair and inclusive workplace. They also noted that many organizations struggled with how to turn their desire to help into action: many counselled that a declaration of intent to hire wasn’t enough, that “aesthetic diversity” or tokenism could inadvertently cause harm to relevant employees, and that it was important to hire and promote Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC) leaders and board members into roles with the power to make organizational change. Others commented that internal bias and micro-aggression training for all staff was an important complement to equitable hiring.

Employer Survey: A Snapshot of Early Findings

The ICTC Equitable Rebound Employer Survey (n = 503), hereafter referred to as “employer survey,” was delivered across Canada to persons in roles responsible for hiring and people management in companies with at least 50 personnel. Respondents held managerial roles (42%), director roles (20%), C-level, president, or vice president roles (20%), owners (6%), and HR professionals or hiring managers (12%). Just over half of respondents identified as men (55%), and just under half as women (45%), while fewer than 1% identified as gender non-conforming or non-binary.

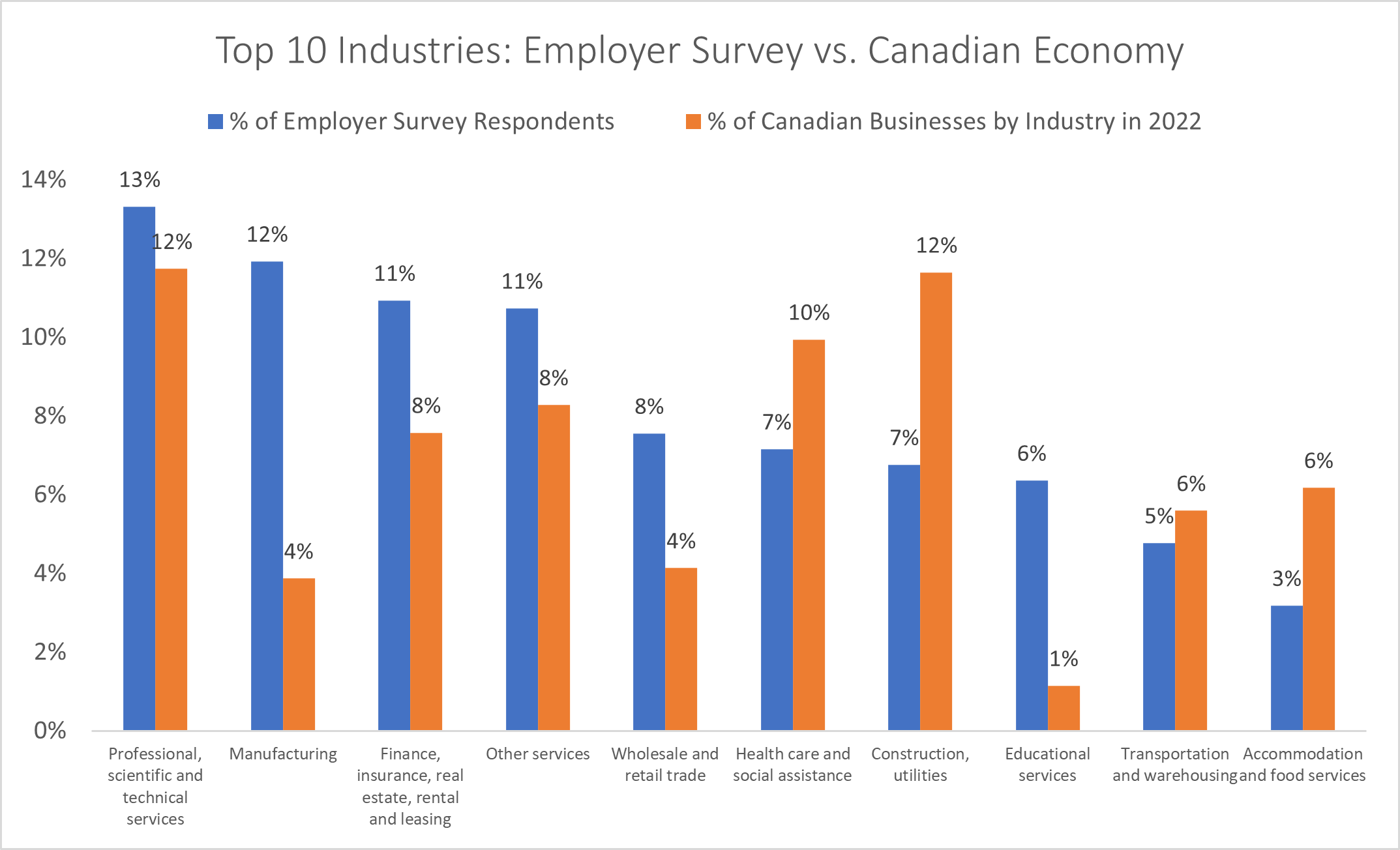

Compared to the Canadian economy, the ICTC employer survey overrepresents respondents from Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services; Manufacturing; and Finance, Insurance, and Real-Estate; as well as Wholesale and Retail Trade and Educational Services. Furthermore, the survey underrepresents respondents from Health Care and Social Assistance, Construction and Utilities, Transportation and Warehousing, and Accommodation and Food Services (see Figure 3). Just under half of the respondents (41%) were from large companies of at least 500 personnel. This marks another large difference between survey respondents and the economy as a whole: most Canadian businesses are very small (1-4 personnel). About a third (35%) of respondents were from medium-sized businesses (100-499), and a quarter (23%) came from businesses of 99 or fewer.

Large businesses are responsible for the highest proportion of employment in Canada: companies of 500+ personnel employed 46% of Canadians in 2022. Accordingly, while ICTC’s employer survey data should not be used as a proxy for the Canadian economy, respondents describe policies impacting many jobs. Predominantly, respondents are from larger companies in the professional, financial, technical, and social services sectors, manufacturing, and trade. As personnel from larger companies, employer survey respondents are a unique sample of people managers and hiring managers with resources to implement inclusion training and other related policy.

Figure 3: Top 10 2-Digit NAICS, Employer Survey vs. Canadian Economy. Canadian Economy Data Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Business Counts, with employees, December 2022: Table 33-10-066-01, 2023-02-20.

Hiring Priorities: The Question of Culture Fit

When given a list of attributes and asked to evaluate how important each was to the hiring process:

- 94% of respondents ranked “how well the individual will fit into company culture” and “the soft or human skills the individual has for the position” as somewhat or very important, and 93% ranked technical skills similarly highly

- 92% of respondents agreed that the candidate’s confidence in their skills was somewhat or very important

In the first Equitable Rebound project advisory committee meeting, participants noted that “culture fit” can inadvertently introduce biases, with one person saying that “cultural fit can mean people that look and sound like me.” Similarly, employer assessments of “soft skills” can reflect encoded biases and evaluations of “confidence” can be skewed by variables like accent and gender.

In addition:

- 83% agreed that education level was important

- 82% agreed that the right degree program/field was important

- 74% agreed that the candidate’s ability to start right away was important

- 62% agreed that referral from a trusted source was important

When asked how they evaluate culture fit, most companies used interviews (75%) and/or a meeting with other team members (43%), while many others relied on reference checks (56%). About a quarter of respondents reported administering some type of aptitude or personality test (27%, and in companies of 500+, 32%). A small proportion of respondents that selected “other” explained that they used security/background checks, a probationary period, or a social media check to assess culture fit. All told, there are many ways for conscious and unconscious employer biases to enter hiring processes: through their evaluations of culture fit, soft skills, confidence, credentials, and a candidate’s access or lack of access to referrals and important professional networks.

Diversity and Inclusion Targets: When Do They Exist, and How Do Organizations Hold Themselves Accountable?

In an open-ended question, respondents were asked to name any existing diversity and inclusion targets set by their organization. Overall, only 28% said they had targets of some kind: this was more common in larger than smaller companies (31% of companies over 500 vs. 20% of companies 50-99). Of companies with targets, however, about a third simply said that their aim target was to create an equal opportunity for all and that they primarily based evaluations on qualifications. A further 23% simply said they had targets but didn’t specify what they were. Accordingly, a very small number of participants reported having tangible targets related to diversity and inclusion. Of the entire sample, about 6% (n = 28) discussed some kind of goal related to different cultures or racialized persons, 2% (10) talked about setting gender diversity targets, and one person discussed setting targets related to age.

In some cases, employer responses articulated unambiguous targets, such as:

“25% of employees are visible minorities”

“50% men/50% women”

“Avoir une corrélation entre nos effectifs et la population” [to have a correlation between our workforce and the general population]

“Je ne les connais pas toutes par cœur, mais ce sont les critères fixés par le syndicat et le secteur des ressources humaines. (Ratio hommes/femmes, absence de discrimination vs les handicaps/ origines ethniques etc.)” [I don’t know them all by heart, but these are the criteria set by the union and the human resources sector. (Ratio men/women, absence of discrimination with regard to disability/ethnic origins etc.)]

A small number of these alluded to targets attached to seniority: for example, “Yes, we are now requiring certain senior roles to be filled by a visible minority.”

Conversely, many expressed a desire to have a more diverse workforce but found targets difficult to implement due to a tight labour market or uncertainty about implementation:

“Nous considérons la diversité comme un élément important. Ceci fait partie de nos objectifs sans avoir de chiffre précis” [We consider diversity to be an important element. This is one of our objectives without having a precise figure.]

Other employers expressed confusion at why targets might be helpful or frustration that targets might interfere with their ability to hire the best person for the job. Referring to targets or quotas, one employer said: “No…We hire the best candidate, period.” Another commented, “On choisi le meilleur candidat peu importe race, couleur ou genre” [We choose the best candidate regardless of race, colour or gender.] In qualitative interviews with experts in equitable employment, several noted that employers might not notice that their outreach strategies, de-facto networks, or job post contents were creating a candidate pool that lacks diversity. Organizations with diversity targets, if approaching the task genuinely, are likely still hiring the most qualified person for the role but putting in time and effort to ensure that their organization’s reputation, networks, and application processes are inclusive and attractive.

When asked how their organization stays accountable to diversity and inclusion targets, most respondents with diversity and inclusion goals said the responsibility rests with the human resources department (62%). Other common responses included an internal management review (38%), a year-end employment audit (35%), or an external audit (21%). About one in 10 (9%) of respondents with diversity and inclusion targets admitted they didn’t do anything to stay accountable.

Training in the Workplace

About two-thirds (68%) of employers surveyed provided some kind of training for equity, diversity, and inclusion in their workplaces, and large companies (500+) were significantly more likely to do so at 77% (compared to 58% of companies of 50-99 and 64% of companies 100-499).

The most common types of EDI training provided are:

- Anti-racism Training, 31% of respondents (more common in larger companies at 39% compared to only 17% for companies under 100 people)

- Cultural Safety Training, 24% of respondents

- First Nations, Metis, and Inuit cultural awareness training, 23% of respondents (more common in large companies at 32% for companies over 500, compared to only 9% of companies under 100)

- EDI Training for People Managers (23%) or HR Personnel (22%), both more common in large companies; or all staff during onboarding (23%)

Demographic Data Collection

For employers to be able to commit to equity targets (including ones pertaining to advancement, equitable promotions, and pay equity), some type of demographic data needs to be collected. However, organizations may or may not know how to collect data appropriately, how to store it confidentially, and what to use it for.

Employer survey respondents were asked about demographic data collection (voluntary/opt-in) for new candidates and for existing staff.

Table 1. “When hiring for a position, does your organization collect any of the following from potential candidates through an optional candidate self-declaration form?” (* indicates when the % of companies in the 500+ category is significantly higher than the % of companies of 50-99 personnel).

| Type of Candidate Data | % of Companies 50-99 | % of Companies 100-499 | % of Companies 500+ | % of all Respondents |

| Citizenship or status | 26% | 31% | 44%* | 35% |

| Age | 28% | 32% | 31% | 31% |

| Gender | 22% | 32% | 32%* | 30% |

| Ethnicity | 8% | 23% | 28%* | 21% |

| Disability or neurodiversity | 9% | 19% | 27%* | 20% |

Table 2.“Does your organization collect any of the following from existing staff through an optional self-declaration form?” (* indicates when the % of companies in the 500+ category is significantly higher than the % of companies of 50-99 personnel).

| Type of Staff Data | % of Companies 50-99 | % of Companies 100-499 | % of Companies 500+ | % of all Respondents |

| Citizenship or status | 16% | 29% | 28%* | 25% |

| Age | 18% | 27% | 27% | 24% |

| Gender | 12% | 25% | 29%* | 24% |

| Ethnicity | 10% | 18% | 28%* | 20% |

| Disability or neurodiversity | 8% | 19% | 22%* | 17% |

Finally, and most importantly, respondents who did collect demographic data were asked what they used this data for. About 15% said they collected it but didn’t use it, and 5% said they weren’t sure.

Respondent organizations with demographic data were using it to:

- Monitor employee diversity (37%)

- Monitor pay equity (32%)

- Monitor promotions or advancement for equity (30%)

- Or, for organizational quota purposes (28%)

Importantly, demographic data can be collected well or poorly (and used well or poorly). In Disaggregated demographic data collection in British Columbia: The grandmother perspective, the BC Office of the Human Rights Commissioner (BCOHRC) writes that “by making systemic inequalities in our society visible, data can lead to positive change; the same data used or collected poorly can reinforce stigmatization of communities, leading to individual and community harm.” Small organizations may have a difficult time anonymizing data or making assessments about how well their organizations are doing on EDI targets if they have a small team and prefer a relationship-focused and qualitative approach. Larger organizations more often have the capacity to implement disaggregated demographic data collection policies respectfully and have begun to develop more sophisticated approaches to monitoring who is typically hired, promoted, and retained and in what types of roles. As one interviewee in a study on Indigenous leadership in technology in BC noted:

“We did an internal demographic assessment within our HR system… Doing this through HR allows us to dig into inclusion, not just representation. This lets us ask not just, Are we hiring diverse employees? but How are we hiring people? What types of roles? How are we compensating people, average performance rate by identity, if we have biases in their processes that will lose us people in retention…Quotas are not the ultimate goal.”

Using demographic information as a cause for action and change was a key takeaway from the Indigenous Leadership in Technology study, rather than collecting data simply to keep. Monitoring advancement and management or sponsorship and finding ways to support more Indigenous, Black, and racialized leaders in an organization is crucial. In this study, many women raised the topic of sponsorship and mentorship and its importance to their career goals, tying back to the intersection of gender and racialization in how soft skills, confidence, and self-advocacy are perceived in the workplace. Some interviewees identifying as women highlighted sponsors as particularly critical due to the risk of being penalized for self-advocacy. Accordingly, disaggregated demographic data information also allows HR to confidentially examine the hiring and promotion habits of managers in a large enough organization.

Experiences of Career Advancement and Reinvention for Indigenous, Black, and Racialized Communities Following the Pandemic

The following snapshots illustrate the type of feedback ICTC received on research participants’ lived experiences over the past three years. A more fulsome analysis of the extensive primary research conducted in this study will be included in the final report.

Remote work is a game-changer for access to career advancement and reinvention.

Work, social capital, and networking have all changed in remote environments. For some, this has made positive changes: for example, several research participants who did not drink alcohol for religious reasons commented that they felt more able to access important networking and decision-making calls, particularly during COVID when nobody was meeting up outside of work. For others, getting face time with their supervisor and creating the type of relationship likely to lead to advancement has proved more difficult. ICTC heard similar feedback from women in mid- and senior-career roles in the technology sector, that virtual networking opportunities have been key to advancement over the last few years but that companies may need to formally institute virtual networking opportunities to avoid inequitable face time between junior and senior staff. People with care responsibilities also reported a wide range of impacts on their lives: for some, virtual work or education made it possible for them to “do it all” while having children. For others, particularly in regions where schools closed, the burden of conflicting responsibilities was too much to manage.

Supports like the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) helped many people weather layoffs; however, some reported uncertainties about accessing CERB.

Not all jobs transitioned to a remote setting. As other research has already demonstrated, Black and Indigenous workers during COVID faced layoffs because their work environments could not transition online. In the face of these jolts to their careers, some participants found ways to go back to school or found a new job. Others struggled to find new work in their area. Several research participants mentioned that they knew CERB existed but didn’t know how to apply for it or had been afraid to apply for it because they felt they would have to pay it back. Unfortunately, many of the participants who reported these issues were people experiencing homelessness. During the initial lockdowns, public library closures created major challenges for people who relied on their public computers or sanitary facilities.

Inflation, and particularly the costs of housing and food, has had a significant negative impact on people already experiencing labour precarity, including their ability to re-enter the workforce in the same or a new field.

In rural, remote, and Northern areas, lack or unaffordability of broadband was also a significant concern for people seeking secure remote employment during COVID-19. In Iqaluit, Inuk participants whose communities had experienced forced resettlement only to be left with insufficient housing, food, and connectivity infrastructure characterized this reality as a part of systemic racism. In Toronto, participants who reported living in urban food deserts echoed similar concerns, highlighting a systemic lack of access to nutritional food, increased housing prices, and the cost of internet within Canada’s largest city. Labour market precarity, limited access to services, and increased cost of living have made sustainable housing and nutrition so difficult that many participants reported experiencing homelessness for the first time at the onset of COVID and not being able to regain their previous lives or start again in a new field.

Figure 4: Community Engagement Event in Iqaluit, NU, Pinnguaq Makerspace, September 2022

Lockdowns and funding crunches made it harder for many community-serving organizations to survive.

Several research participants asked what impact the pandemic had on Indigenous and BIPOC community organizations and what types of funding took priority. Some commented that they felt they had experienced an improvement in funders’ attitudes and awareness of their services. For example, organizations offering diversity, equity, and inclusion consulting or coaching found that there was more interest in their services, though not all companies had budgets to hire them, given the cascading impact of the pandemic. Others commented that closures had impacted them significantly and that transitioning to virtual services had been a real challenge for their organization. Overall, how public funding shifted following the pandemic is a salient topic worthy of further investigation.

For many, health and career planning have become more intertwined than ever before.

Health requirements impacted participants in a wide variety of ways. For some, COVID-19 shone a light on community health needs, and they found themselves pivoting to a mission-driven career. For example, many people we spoke with had spent time reflecting on what their communities most needed and were going back to school for health, education, or social services. Others said that vaccination had different connotations for themselves and their communities. Research by Dr. Jude Mary Cénat recently demonstrated that Black communities in Canada were among the least vaccinated but most affected, in part due to experiences of discrimination in healthcare and the lack of health literature geared to Black communities. Throughout the pandemic, many also noted that a legacy of colonialism and continued experiences of discrimination in healthcare contributes to vaccine hesitancy in Indigenous communities. Choices about health and vaccination have become interconnected with career outcomes over the last few years. Some research participants reported losing jobs because of vaccination status or leaving front-line work because of a desire to avoid exposure to the virus. Many people who left jobs (some to take care of immuno-compromised relatives) were not eligible for employment insurance or CERB.

Looking Forward

Employers increasingly recognize that hiring and promoting more Black, Indigenous, and racialized personnel, including to boards and into leadership positions, is important to their companies for several reasons. In a review of the literature on diversity’s economic impact, the OECD outlines an association between diversity in post-secondary graduates (measured by nationality or place of birth) and innovation (patent applications and grants) in the United States and in Europe. In the technology ecosystem, ICTC has noted that the inclusion of people with diverse lived experiences helps companies be more innovative and plan for responsible innovation and safety by design. Others have suggested that collaboration in diverse teams is even associated with better investment decision making. And finally, a clear takeaway is that firms without the right strategies to hire newcomers, women, and BIPOC candidates will, as the OECD puts it, “increasingly feel the cost of discriminatory behaviour in the context of growing labour market shortages.”

For job seekers from equity-seeking communities, access to career planning tools, mentors, sponsors, and education is a significant part of supporting individual advancement and mobility. However, enabling infrastructure is even more important, as it creates the conditions that allow people to shape their own futures without financially struggling to survive. Overall, the pandemic shook the foundation of enabling infrastructure like public services, and community-serving organizations while threatening jobs and compounding existing restrictions to people’s ability to shape their own careers—restrictions already more present for Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities in Canada. While many people have advanced or pivoted to a career in which they are thriving, enabling infrastructure must restore the foundation (and raise the floor) of everyone’s ability to determine their own career path. In light of recent advancements in technology that have enlivened the debate on automation in the workplace, supporting everyone to build resilient, transferable skills and the tools to shape our own futures is more important than ever.

Call for participation: If you are a Canadian employer interested in talking about your programs and policies, or a person identifying as Indigenous, Black, or racialized living in Canada, we would love to talk to you. Please get in touch with us by emailing the Research and Policy team at @email.