Canada’s Pacific melting pot province of British Columbia is rich in natural beauty, resources, and talent. Compared to Ontario and Quebec in particular, the province has so far managed to avoid a large number of COVID-19 infections and has suffered less economic damage as a result. Credit may be due to the smart policies BC enacted quickly, such as preventing nursing-home staff from working in multiple locations.[1] Nevertheless, the economic shock from COVID-19 is enormous, and it remains to be seen how the economy will recover, and how society will restructure itself following the shock. This blog discusses the state of the BC economy pre-COVID and post-COVID.

BC’s Economy, Pre-COVID

In recent years, British Columbia’s economy has outperformed most other Canadian provinces. BC’s inflation-adjusted GDP expanded at a very impressive annual rate of 3.3% between 2014 and 2017. Indeed, from 2010 to 2018, inflation-adjusted GDP per person grew by 11%, faster than any other province (Figure 1). Compared to other regions of Canada, British Columbians have been creating considerably more economic output per person over the past decade, which is intimately connected to prosperity.

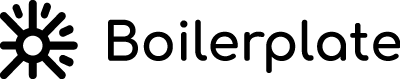

Figure 2 reveals the distributional changes in employment in the province in recent years. The figure shows that South Coast employment is the only region growing at a faster rate than employment in the province as a whole. Thompson Okanagan, Vancouver Island and Sunshine Coast, and the North East have grown nearly as fast as the province as a whole, while the Kootenay and Cariboo are essentially stagnant, not growing over the past two decades or shrinking slightly. Employment in North Coast and Nechako has declined by about 17% over the past two decades, however, business activity related to the $40-billion liquefied natural gas terminal project in Kitimat may improve the employment outlook in this region.

Figure 3 shows sectors by the percent of total employment in BC versus Canada prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 3 shows sectors by the percent of total employment in BC versus Canada prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (only sectors that unusually dominant in BC are compared to the rest of the country).

What the figure reveals is consistent with general intuitions about the province. In Canada, restaurant and bar staff represent just over 6% of all employees, whereas in BC the number is about 7.6%, a substantial difference. Likewise, construction, real estate, and accommodation are disproportionately large, as are all sectors tied to BC’s substantial number of building development firms (operating within the province and outside of it). Tourism is among these sectors, alongside amusement, gambling, recreation, air transportation and sightseeing transportation — all disproportionately large in the province. The figure also includes technology-related sectors, including film and sound recording, telecommunications, and electronics sectors. Several natural-resource sectors, especially forestry and logging, wood-product manufacturing, mining and quarrying are disproportionately large. Greater Vancouver’s position as Canada’s largest port, along with the port city of Prince Rupert, means that water transportation, warehousing and storage, and transportation support sectors are significant in the province.

Wages

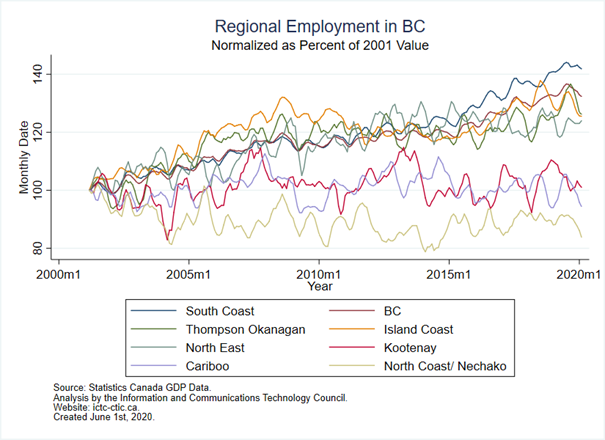

Statistics Canada maintains detailed data on wages across provinces and occupations, which provides insights on a variety of characteristics. Figure 4 shows that median hourly wages in BC in 2019 were second only to Alberta among the provinces and now stand above $25 per hour.

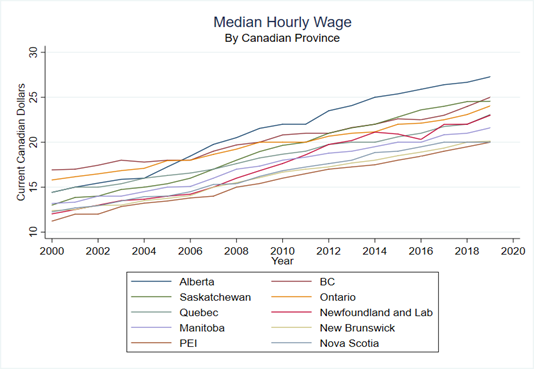

Finally, Figure 5 shows the median hourly wage by industry in BC in 2019. Industries with many high-skill professional or technical and trades workers are the most well remunerated, including those in utilities, mining and quarrying, public administration, and professional or scientific services. Industries with many lower-skill workers receive the lowest wages, including food and accommodation, retail, and agriculture. Wages for the digital economy are estimated to be roughly $77,000, surpassed only by utilities, and mining, quarrying, oil and gas.

Impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 is likely the largest shock to British Columbia’s economy since the end of the Second World War. While the province has been relatively successful in preventing the spread of the virus, certain large and vulnerable sectors, such as food and accommodation, tourism, and film sectors, have been impacted. The province’s robust real estate and construction industry has also slowed considerably. As shown in Figure 6, investment in building construction plunged 26% to $1.5 billion in April compared with the previous month in British Columbia.[2]

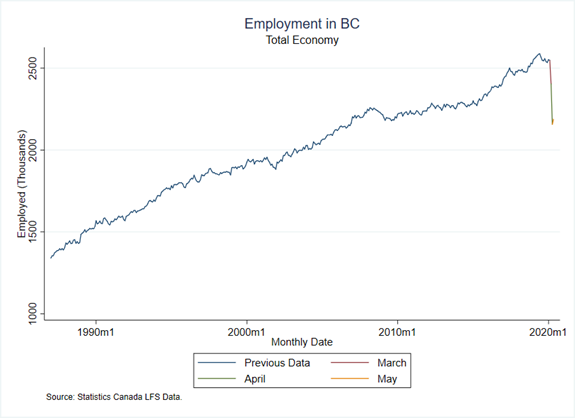

March and April were both the largest one-month drops in official employment figures since the start of the modern version of Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey in 1976. Combining the drops of March and April, a total drop of 15% in total jobs occurred. Figure 7 shows that employment in BC is now at its lowest level since 2006.

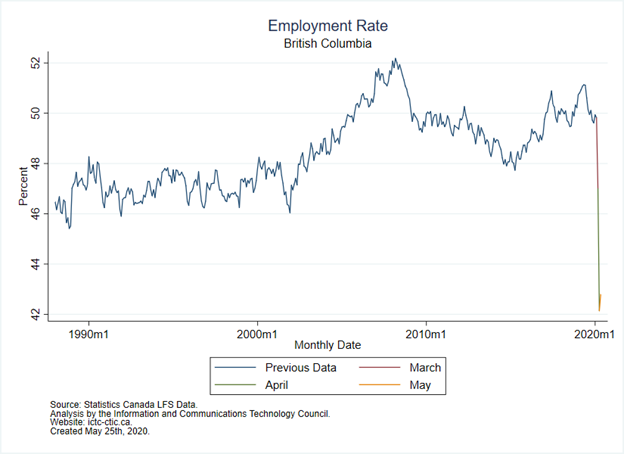

The population of BC has grown by nearly 25% since 2006, which is reflected in a current payroll employment rate plunge to 43% from 49%, shown in Figure 8.

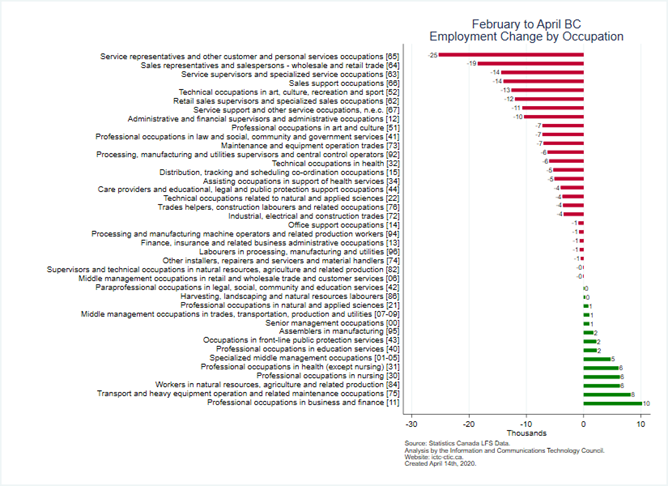

BC’s losses have been concentrated in the relatively large Food and Accommodation sector. Figure 9 shows that from February to April, 25,000 service representatives and customer services jobs were lost. Sales, retail, and technical or maintenance categories also lost thousands of jobs. Meanwhile, nurses and various professional business occupations saw job growth during this period.

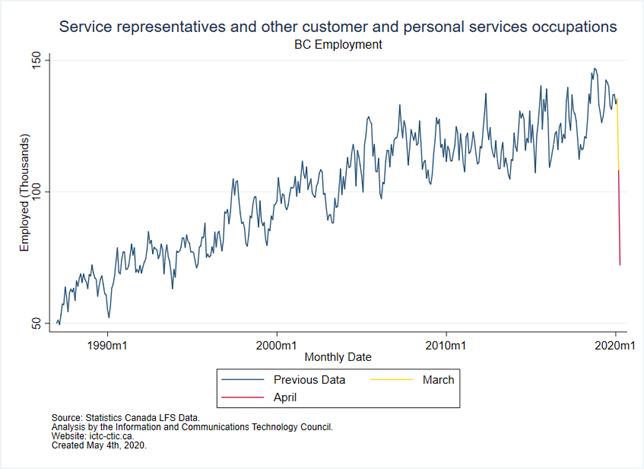

Figure 10 reveals the two-digit NOC code with the largest two-month drop: customer service representatives. The employment level in March and April fell to mid-1990 levels. These roles were lost, as many retail and restaurant establishments were closed (but are likely to return as the economy reopens).

BC’s Economy, Post-COVID

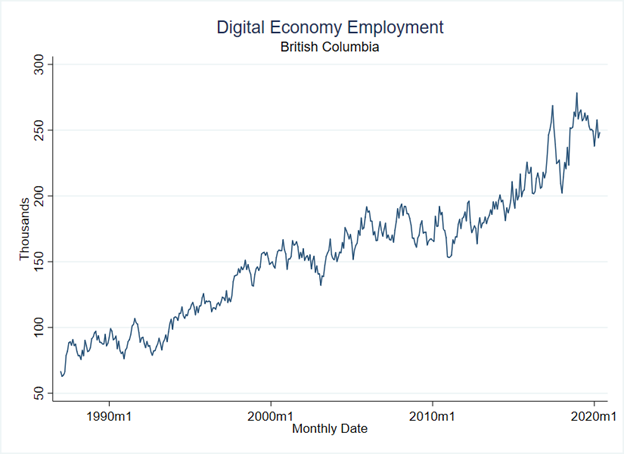

ICTC measures the “digital economy” as the union of “digital occupations” and “digital industries.” Therefore, a human resources worker at a tech startup or a programmer at a bank would be included in the digital economy. In BC, employment in the digital economy has outpaced growth of the general economy. Figure 11 shows the growth of the digital economy from less than 100,000 workers in the early 1990s to roughly 250,000 workers today.

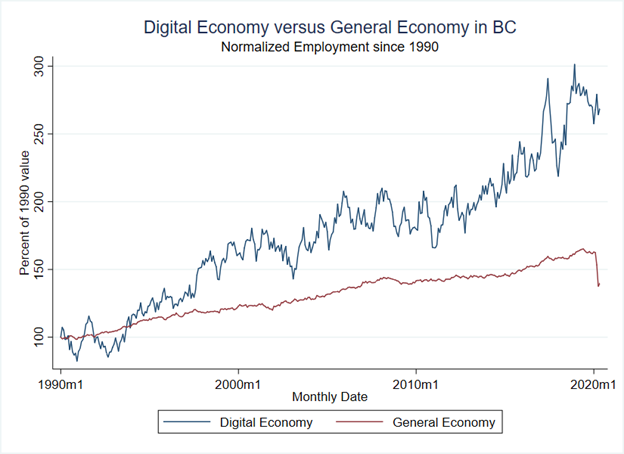

Figure 12 reveals that the digital economy has outstripped employment since 1990 in British Columbia. The graph plots normalized employment (allowing for the valid comparison of data over time). The figure shows the digital economy in BC surged from 1990 to roughly 2000, when the dotcom crash occurred. From 2000 to roughly 2012, the digital economy grew at approximately the same pace as the general economy. Then from 2012 to the present, the digital economy again surged at a rate much faster than the general economy as Vancouver solidified its position as a tech hub.

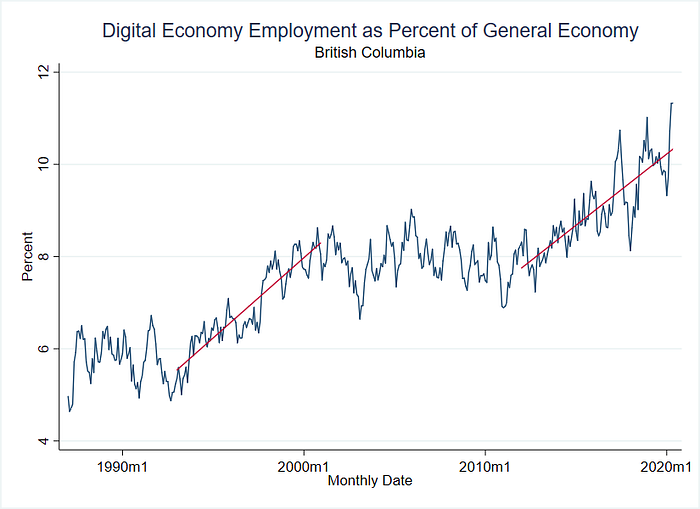

Figure 13 shows employment in the digital economy as a percent of the general economy since the mid-1980s. The figure clearly shows the two periods of rapid growth in the technology and innovation sectors in British Columbia: once from 1993 to 2000, and again from 2012 to 2020. Indeed, the impact of COVID-19 has been to increase the relative share of the digital economy in British Columbia to date. It now stands above 11%.

The figures reveal that the digital economy has not been adversely affected by COVID-19 or the resulting lockdowns of the economy. This is likely because demand for digital economy services has heightened during the pandemic (online entertainment, ecommerce). The digital economy production process is also less affected by lockdowns, as most digital economy workers are able to perform their jobs remotely. Therefore, the digital economy is likely to offer a path forward for BC’s economy as the COVID crisis gradually resolves. Resiliency to shock, high wages, and growing employment mean that BC’s digital economy will likely remain a bullish sector for the near future.

[1] Kathryn Tindale, “Care home staff to work at only one site as COVID-19 deaths in B.C. reach 50,” CityNews 1130, Apr 9, 2020, https://www.citynews1130.com/2020/04/09/covid-cases-bc-update/

[2] “Investment in building construction, April 2020”, June 22, 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200622/dq200622a-eng.htm