ICTC Overviews summarize findings from full-length studies. To read the original report, visit it here.

Study Scope

This study explores the implications of the growth in remote work and the post-COVID gig and sharing economies.

Loading: The Future of Work defines and discusses key concepts in this labour market transformation and the opportunities and challenges for creating a resilient and inclusive economy.

It also looks at key regulatory considerations for the gig economy.

Study Context

Gig work expanded following the 2008 financial market crash, when people turned to online platforms like askRabbit to fill income gaps.

In 2020, the spread of COVID-19 has been dubbed the world’s “first mass experiment in remote work.”

- Advocates of remote work cite studies of overwhelming worker support for extending work-from-home arrangements beyond the pandemic. Most workers are confident they can perform as, or more, effectively working remotely.

- Critics point to growing class divisions between those who can work remotely (often full-time workers with secure employment); those who cannot, such as workers in food, transit, sanitation, etc.; and precarious gig workers who often lack job security, paid sick leave, health insurance, and employment benefits.

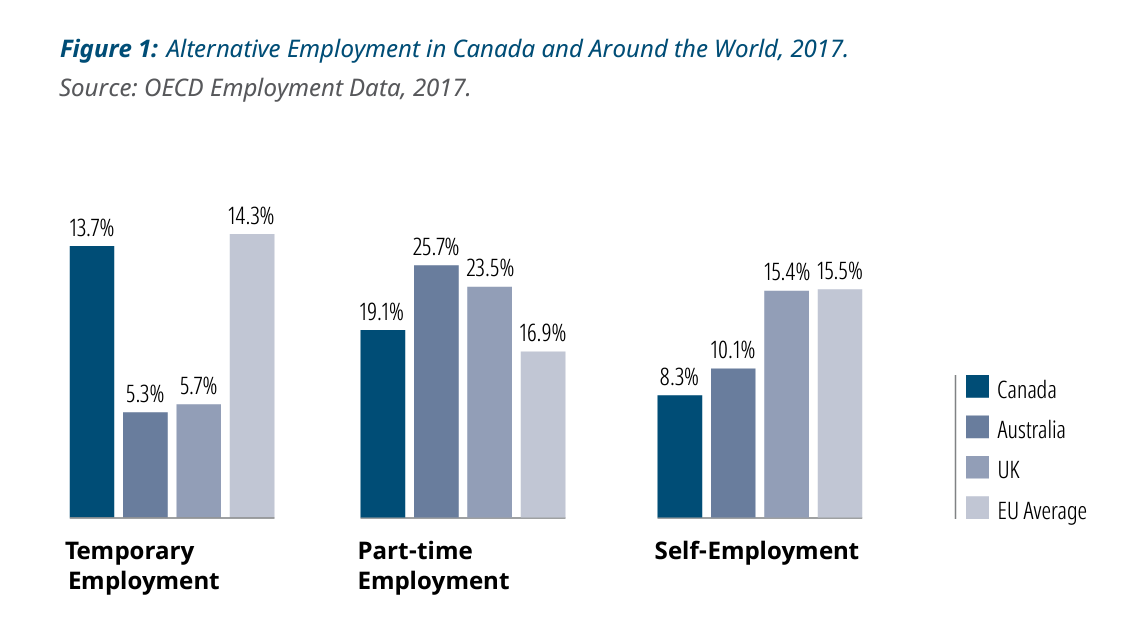

More than 40% of the Canadian workforce was employed on a non-permanent basis in 2017. The rise of new digital platforms is accelerating self-employment and temporary work.

Key Definitions

Gig Economy: informal paid work enabled by online platforms (eg. Freelancer.com, Upwork, TaskRabbit, Amazon Mechanical, Fiverr, etc.)

Gig Worker: all workers regardless of sector, working on short-term contracts, including independent agents and contractors

Sharing Economy: all economic activity based temporary use of a product or service, utilizing digital platforms (eg. Uber, Airbnb, DogVacay, Turo, JustPark, etc.)

Photo by Simon Abrams on Unsplash

Study Findings

Impact of COVID-19

From March to May 2020, COVID-19 lockdowns reduced overall employment in Canada by 3 million.

Work shifted to online. In the US, on March 30, 2020, over 62% of US workers were working remotely compared just over 30% in 2015.

- Workers with higher education were much more likely to work remotely than those with a high school education or less: 83% vs 35% (Massachusetts-based study)

Productivity

A PwC survey of over 850 CFOs in 24 countries found that productivity levels remained relatively stable from March to May 2020.

- Nearly half of CFOs surveyed are considering permanent remote work arrangements, where possible

- 72% believe COVID-19 flexibility measures will benefit their companies in the long term

Gig Economy Trends

The gig economy opens new economic opportunities for people of various ages, skills levels, lifestyles, and regions.

- In 2016, Statistics Canada reported nearly 10% of the Canadian population aged 18 or older participated in the sharing economy. A recent PwC report anticipates that to rise to 50%

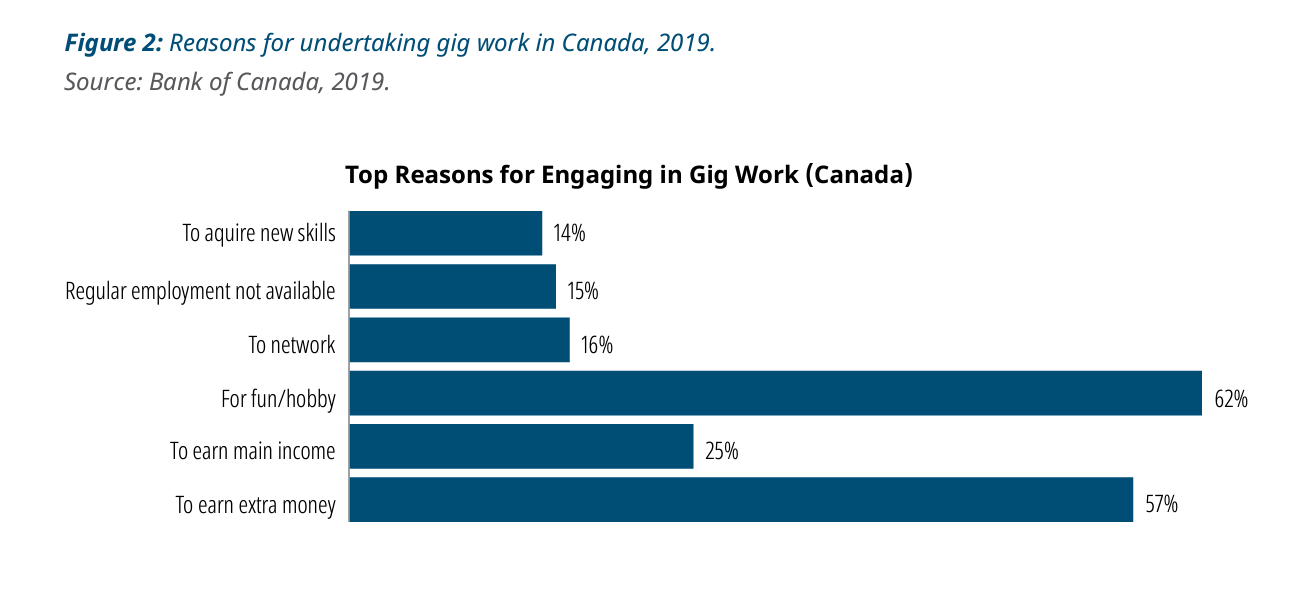

- A 2019, a Bank of Canada study estimated that 30% of Canadians participated in some form of informal work (3.5% participated in gig work, often via online platforms)

COVID-19 is dampening the demand for sharing-economy services, whereas highly skilled contractors with in-demand digital skills are able dictate prices and pick jobs. “Essential” gig workers face increasingly precarious conditions.

Shift Away from Traditional Work Arrangements

Economic volatility and the growing participation of a younger workforce have spurred a shift away from long-term work relationships. Digital platforms are accelerating self-employment and temporary work.

Gig Economy Shortfalls

According to a Doteveryone, the gig economy suffers from significant shortcomings, including a lack of financial security for workers, a loss of dignity at work, and the inability to progress in a career.

- An average Uber driver in the US earns between $8.55 and $10 an hour after deductions while the average full-time taxi driver earns $17 an hour

- Low pay for low-skill gig work eliminates one of the top benefits of gig work: flexibility. To earn a meaningful renumeration requires working many hours

- Many “essential” gig workers during the pandemic face greater risk of exposure to the disease

High Demand Skills

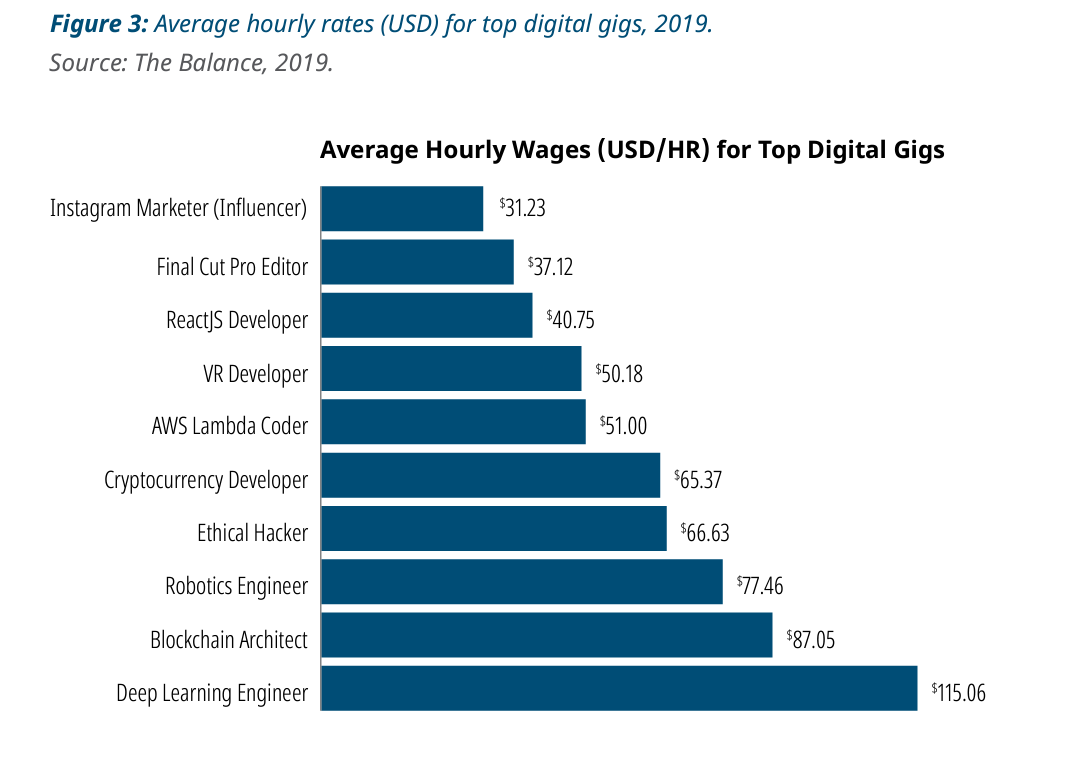

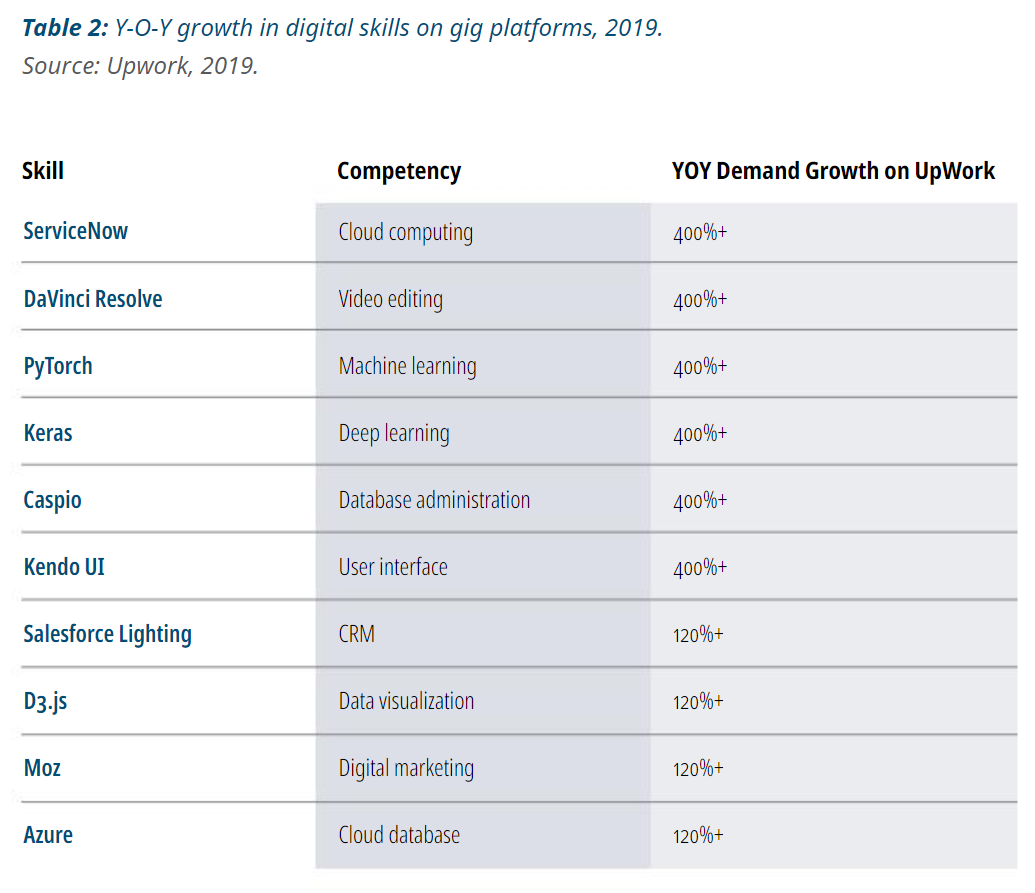

Digital platforms can also immensely benefit gig workers with in-demand digital skills.

According to UpWork, most of the top-ranking skills on the platform in 2019 were digital. Demand for some skillsets rose by 400% year-over year.

Generational and Lifestyle Factors

Flexibility is a key driver for gig economy participation. A survey of BC gig economy workers found 70% ranked flexibility over earning more money through full-time work.

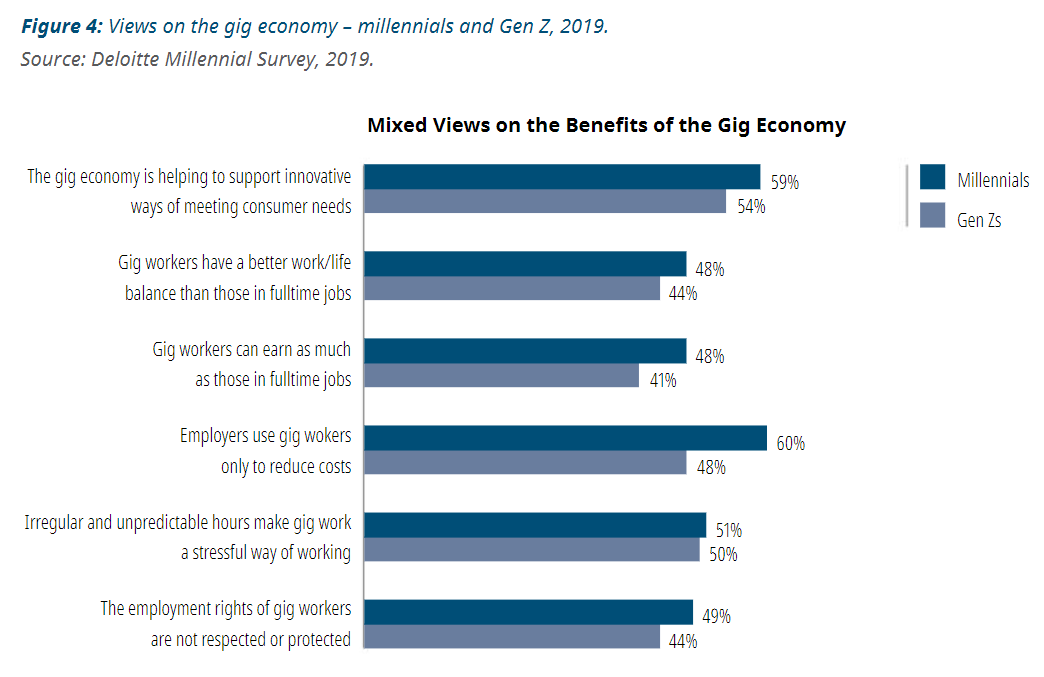

Flexibility is also valued by younger workers in full-time jobs. Deloitte’s 2019 Millennial Survey found most people look to the gig economy for supplemental employment, not full-time employment.

Gig economy participants are mostly young workers, but increasingly gig work is a viable option for aging workers and those re-entering the workforce after time off.

- According to Hyperwallet data, 12% of its 2,000 female gig workers are between 51 and 70

- Uber and DogVacay note that 50% and 25% of their workers are over 50, respectively.

Millennial Perspectives

Millennials and Gen Zs share similar views on the gig economy.

Gig Work Lacks Safety Net

Gig work often provides no employment benefits for full-time workers:

- A US survey of gig workers found only 16% have assets in an employer-sponsored retirement plan, compared with 52% of full-time workers

- Only 39% of gig workers had access to an employer-sponsored health plan, compared to 82% of full-time workers

This lack of retirement planning has significant consequences for state-sponsored healthcare systems, household debt levels, and gig worker retirement capabilities.

Challenges of Rapid Gig Economy Growth

Rapid expansion of the sharing economy in Canada raises the questions of equity and fairness:

- The “uberization” of the economy seems complicit with the rise of precarious gig work

- The main beneficiaries of the sharing economy appear to be wealthy tech-savvy people

A 2019 study found nearly 40% of US families with household incomes of $100,000+ used sharing-economy services, compared with less 20% of families with household incomes below $50,000.

Global Competition for Gig Work

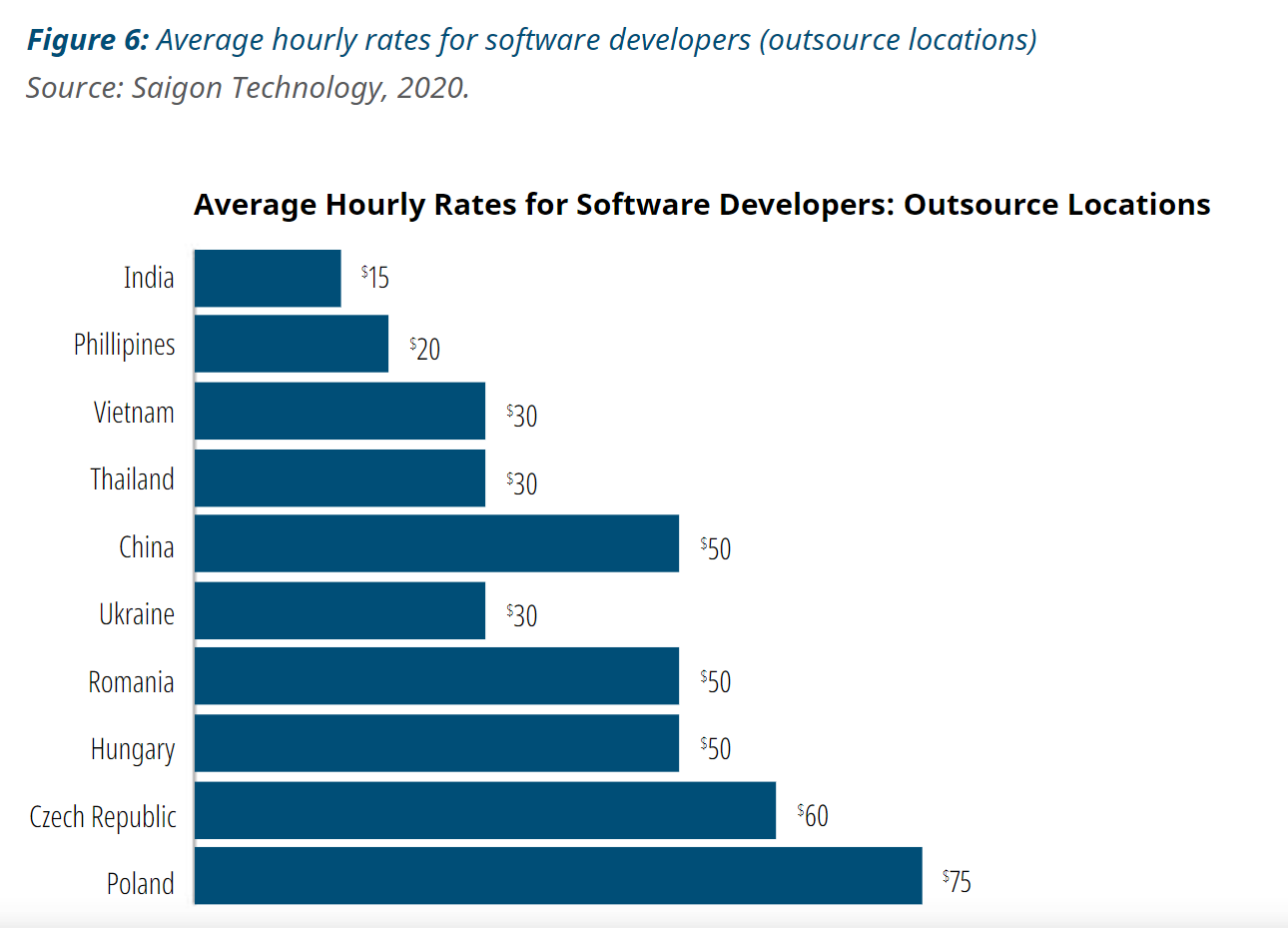

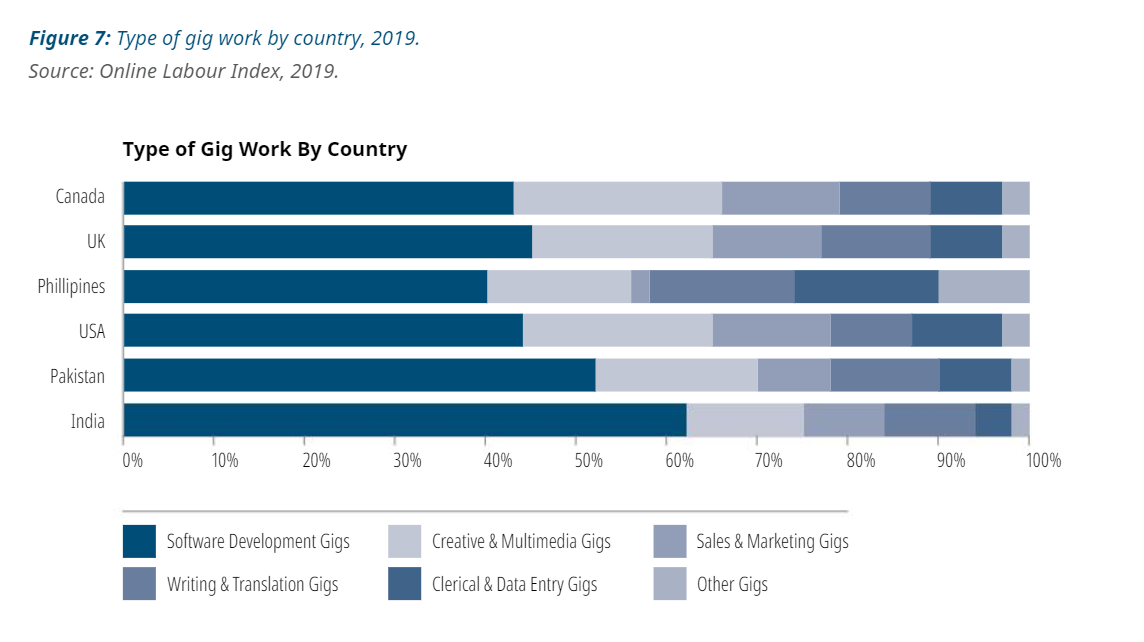

Online gig work and the sharing economy spurs global competition from lower-cost jurisdictions. In 2019, for example, India topped the list of global outsource locations for software development.

The top reason for outsourcing services is to reduce costs.

India shows the highest levels of gig participation in software development, gig work of various kinds is increasingly common globally.

Research suggests global opportunities favour high-skilled and high-demand professionals, however, professions capable of being outsourced will see downward pressure on wages as a result of the booming international market for professional services.

Regulation of the Gig Economy

Appropriate regulation of digital platforms in Canada and for Canadian gig workers will be critical for the growth and development of the gig economy.

Regulatory efforts should align with international efforts and strive to understand the following:

- How Canadian communities can best benefit from digital platform economy development

- How Canada can protect the rights and needs of gig workers

- How to optimize digital infrastructure needs, city planning, and carbon-neutral energy production in a sharing economy

Notable strides in regulation of the gig economy have been made in California and the European Union.

Currently Canada’s Employment Standards Act (governing statuary benefits such as a minimum wage, overtime pay, parental leave, severance pay, employment insurance, etc.) do not extend to independent contractors. Since most gig or sharing-economy platforms hire independent contractors, there is mounting pressure to address the shortfall in employment safeguards.

Gig Worker Unionization

No global body or organization currently represents, addresses, or identifies the concerns or needs of gig workers.

Gig workers in various jurisdictions have sought to unionize, with varying success.

- Food delivery drivers in Japan and Norway were successful in their unionization efforts at the end of 2019

- In January 2020, the United Food and Commercial Workers Union applied to unionize Uber Black (luxury vehicle) drivers in Toronto. If successful, this would mark one of the first examples of unionized gig work in Canada

Other Canadian gig workers are also seeking better representation as a collective.

As work structures continue to evolve, gig workers and employers across jurisdictions will need to adapt to complex new realities.

ICTC Overviews summarize findings from full-length studies. To read the original report, visit it here.