This article summarizes findings from a full-length study. Read the full report here. All figures are contained in full study.

Study Scope

This report investigates the changing patterns, relationships, and norms of work.

The focus is gig and remote work, which are at the heart of these changes and are emblematic of the future of work.

To support the shift to non-standard work arrangements, continued dialogue is needed between workers, employers, and government. This report provides direction for that discourse across a range of issues, including taxation, mental health supports, and opportunities for achieving a more equitable and prosperous future.

The report includes a survey of 1507 individuals, two-thirds of whom were remote or gig workers.

Study Context

COVID-19 has, in part, transformed theoretical debates about the future of work into concrete, immediate issues that require decisions and actions.

Technology is an important driver of workplace changes that allow for greater work flexibility, but a host of other factors are at play in shaping the future of work, including the rise of short-term and task-based employment, weakened unions, and economic concentration.

The “future of work” has become a catch-all term for these (and other) forward-looking labour market topics.

Key Terms

Gig Worker: All workers, regardless of sector, that work on short-term contracts. A gig worker can either be independent, such as a musician or freelancer, or can work as an independent contractor for a gig or sharing economy platform (such as Uber), though the latter is becoming increasingly common.

Gig Economy: Used in the 21st century context, a proliferation of the “informal paid work” enabled by online platforms and spurred by rapidly evolving economic conditions. This is often contrasted to highly structured, formal work arrangements.

Gig Platform: Some gig platforms facilitate interaction and relationship building, but most platforms match providers of services with potential buyers (such as Uber or Airbnb).

Remote Work: The use of technologies and telecommunications to facilitate work outside of the traditional office setting.

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

Study Findings

Increasingly, people are moving away from long-term work relationships in offices to short-term, flexible work that takes place outside the traditional workplace.

“Technology is not replacing work, and indeed cannot replace work in a general sense. It can, however, change the quality of work, for better or worse.”- Jim Stanford, Thinking Twice About Technology Skills

Developments in Remote Work

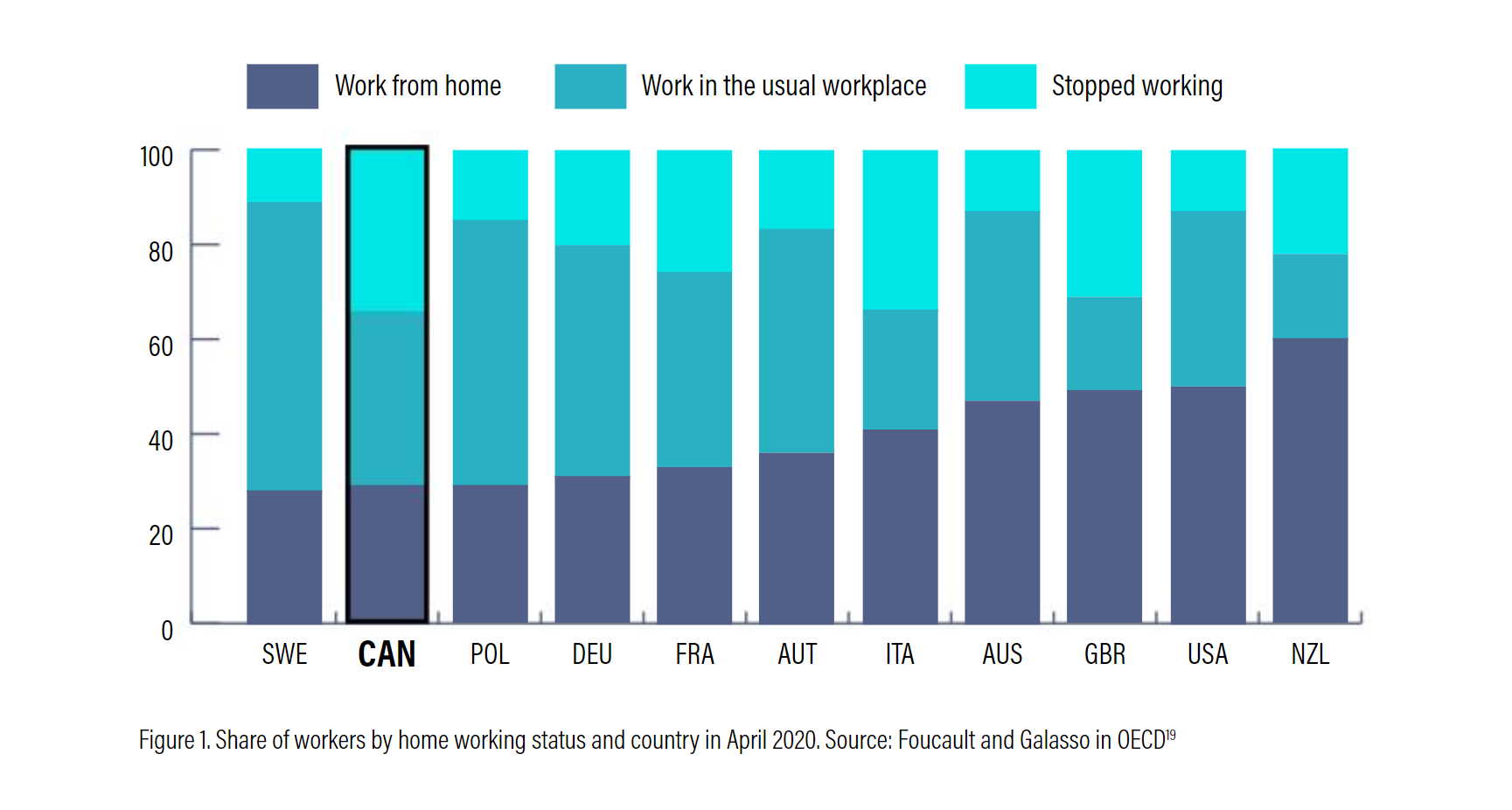

The pandemic has dramatically increased the incidence of remote work in Canada and other countries.

According to Statistics Canada “scheduled [work] hours from home changed very little from 2000 to 2018,” however:

- By February 2020, employees working exclusively onsite at employer premises dropped to 64.9%

- By March 31, 2020, only 40.5% worked exclusively onsite at employer premises

Global comparison of Canadians working from home in April 2020:

According to ICTC’s survey:

- Remote workers tend to feel more positive than the broader workforce

- Remote workers feel satisfied and safe in their roles and believe they strike a good balance between work and home life

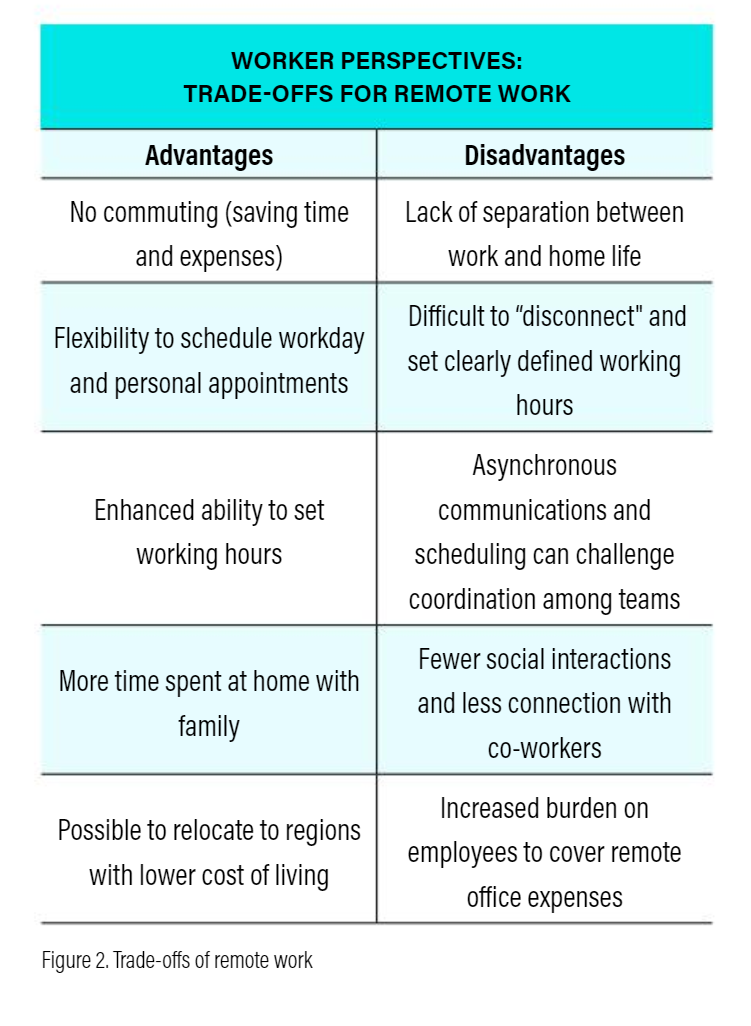

Remote work includes the following trade offs:

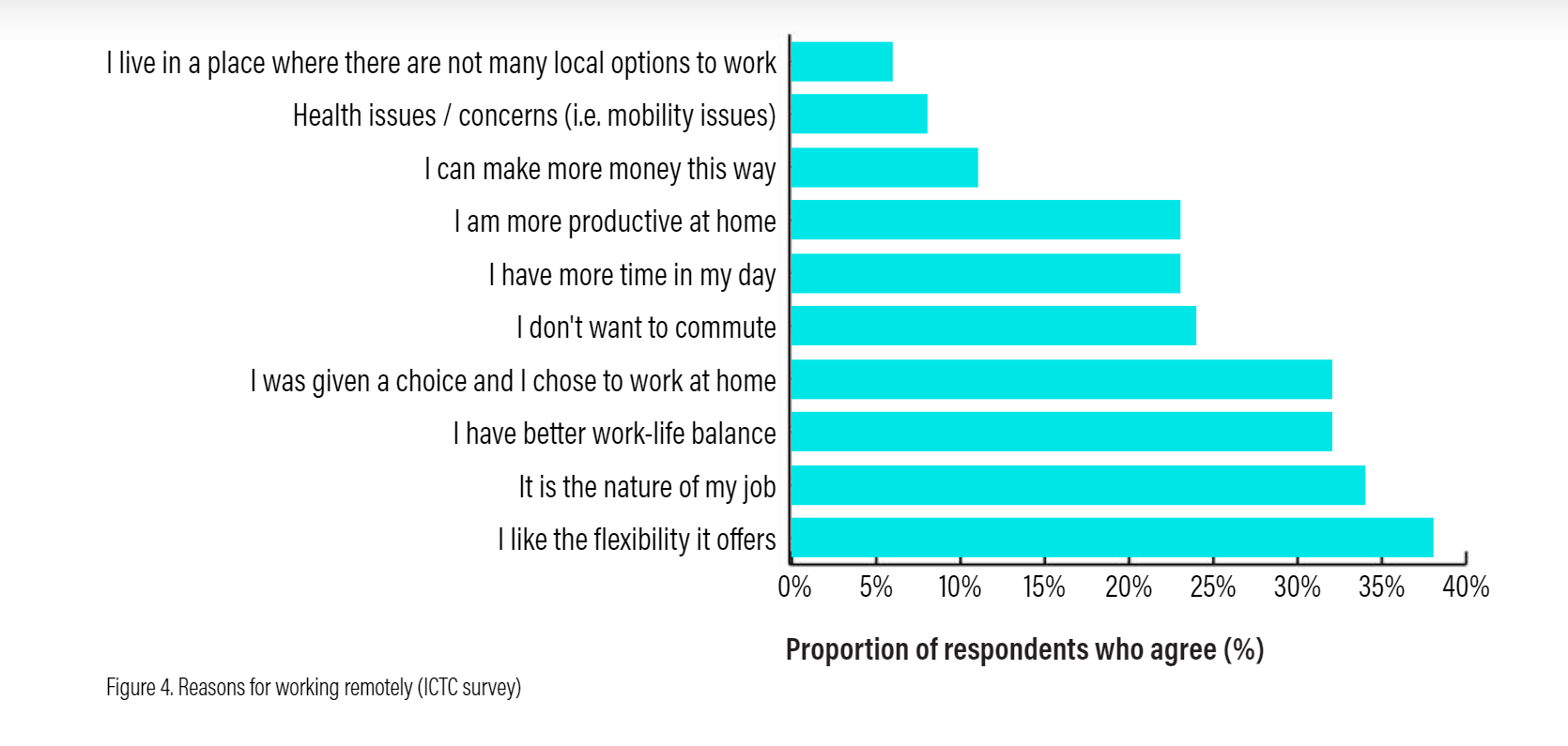

Flexibility is the most cited motivation for remote work, followed by a better work-life balance:

According to Policy Options, one in five Canadians were financially better off during the pandemic, whereas the finances of two in five Canadians deteriorated.

More Productive or Just More Hours?

One of the biggest employer concerns about remote work is productivity. This is what ICTC’s survey of remote workers found:

- 23% of employees who chose to work from home believe they are more productive

- 53% felt they were less productive

Younger workers felt more productive:

- Over half of remote workers under 34 felt more productive

- Less than one-quarter of those over 55 felt more productive

A Statistics Canada study noted that 90% of all new teleworkers reported being at least as productive working from home as from their usual place of work.

Increased remote work productivity could be attributed, at least in part, to employees working longer hours.

Remote Work: Employees Shouldering Expenses

Remote work can result in employees taking on costs such as the additional power, heating, cooling, and internet needs to work from home.

- Remote workers spend approximately 7% more on housing costs than non-remote workers

- Remote employees are paying out of pocket for these and other work-related expenses (furniture, office equipment, or work-related supplies)

An Aon survey of 2,004 HR leaders found in August of 2020 that 42% of companies have implemented, or were actively considering, additional allowances and reimbursement policies (such as temporarily covering cell phone, internet, and home office expenses).

Remote Work by Industry and Role

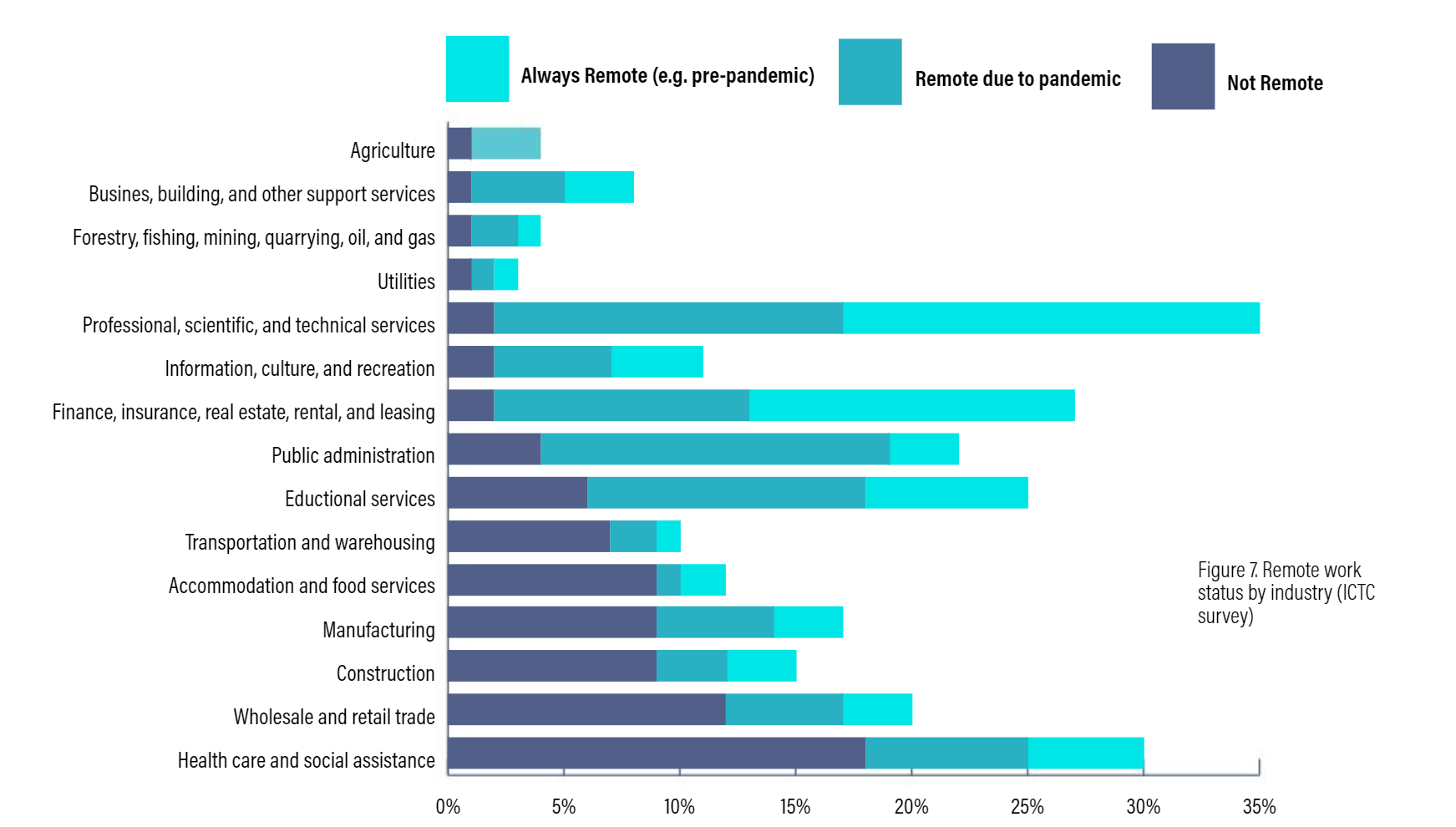

The prevalence of remote work depends on the industry in which work is performed.

The Future is Hybrid

About 70% of Canadian companies are estimated to be considering a post-pandemic remote work plan.

Remote work remains popular among many employees, particularly if it can be combined with office work:

- Almost three-quarters of respondents in a Future Skills Centre study want to continue working from home at least several days a week after the pandemic

Hybrid models, however, could give office regulars an edge over remote workers. The development of in-group and outgroup dynamics can diminish egalitarianism and potentially magnify the gender gap.

Remote Work: The Role of the Government

Large-scale remote work has forced governments to reconsider existing working conditions and labour agreements.

Several countries, including France, Italy, and Slovakia, have passed legislation that gives workers the right to disconnect from work and not engage in work communications during non-work hours.

Similar initiatives are being considered in Canada, with the establishment of a federal Right to Disconnect Advisory Committee and federal consultations aimed at providing federally regulated workers with a right to disconnect.

Taxing Remote Work

ICTC interviewees stated that it is paramount for taxation policy to quickly catch up and clarify the implications of remote work for both employers and employees.

Key areas for consideration include:

- Treatment of workplace expenses and reimbursement

- Tax write-offs

- Changing definitions of “home offices”

- International tax policy

New policies, however, should remain fluid, as remote work continues to evolve.

Remote Work in 2021 and Beyond

Many questions remain about the long-term implications of remote work as the pandemic progresses:

- 70% of surveyed of 350 business leaders are planning for employees to return to the office by the Fall of 2021

- Some employers believe a return to the office will boost teamwork, fluid collaboration, and employee morale

- HR experts and business leaders believe that bringing employees together leads to better engagement, support, group ideation, and social bonding not easily achieved virtually

It is unlikely, however, that employees will want to give up remote work altogether because of the flexibility, opportunity to combine work with caregiving responsibilities at home, and high levels of work satisfaction.

Developments in Gig Work

The global gig economy continues to grow rapidly:

- Estimated gross volume of the gig economy is expected to grow from $297 billion (USD) in 2020 to $455 billion (USD) in 2023

- The use of gig platforms is growing by approximately 26% annually

The Canadian Context

Estimates of the size of the gig economy in Canada varies substantially depending on the definition of gig work:

- Only 8.2% of the working population performs gig work, according to a Stats Canada report

- That estimate climbs to 17% according to the Angus Reid Institute

- And 30%, according to a Bank of Canada study

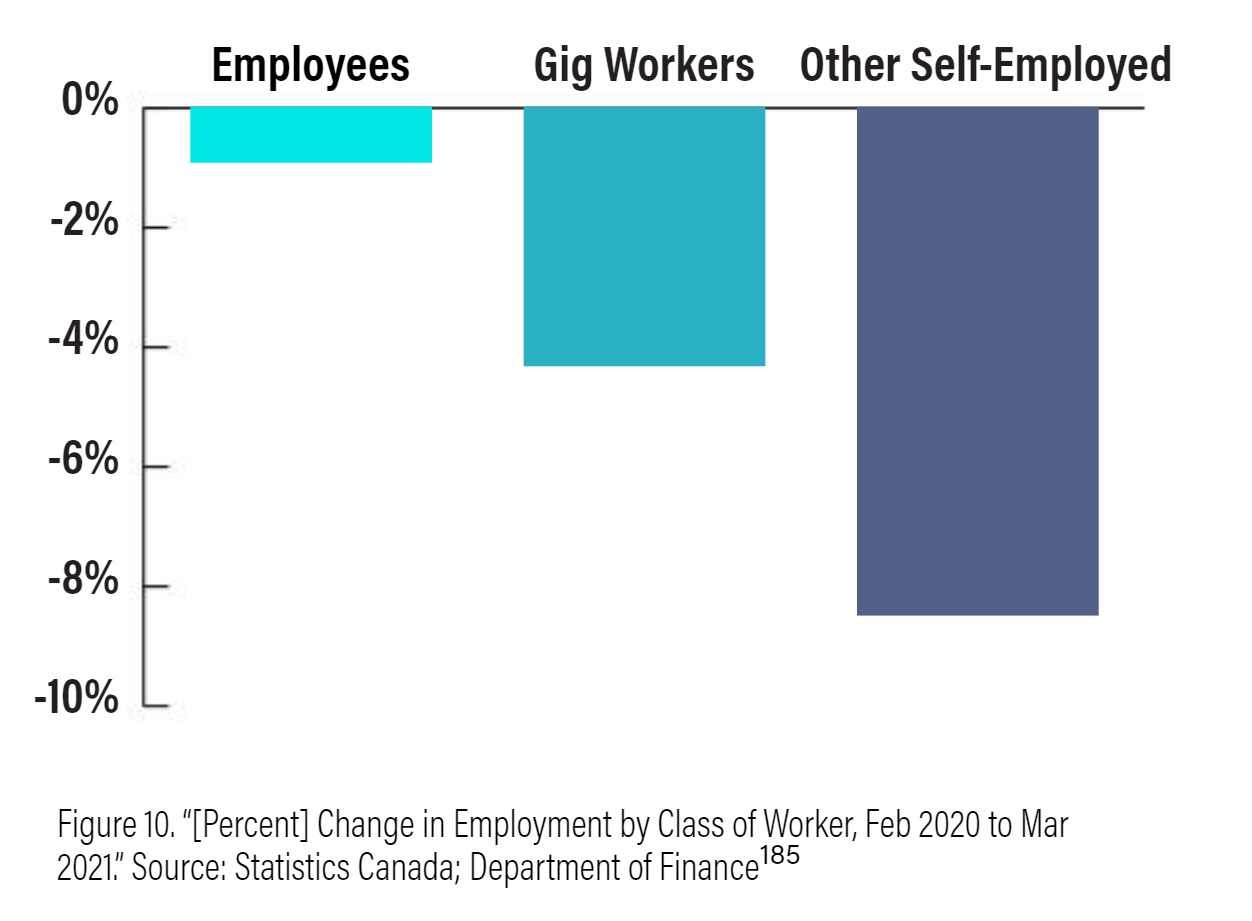

Despite suggestions that the pandemic may have resulted in more Canadians working in the gig economy, Figure 10 below suggests that gig workers lost employment compared to standard employment during the pandemic:

Attitudes About Gig Work

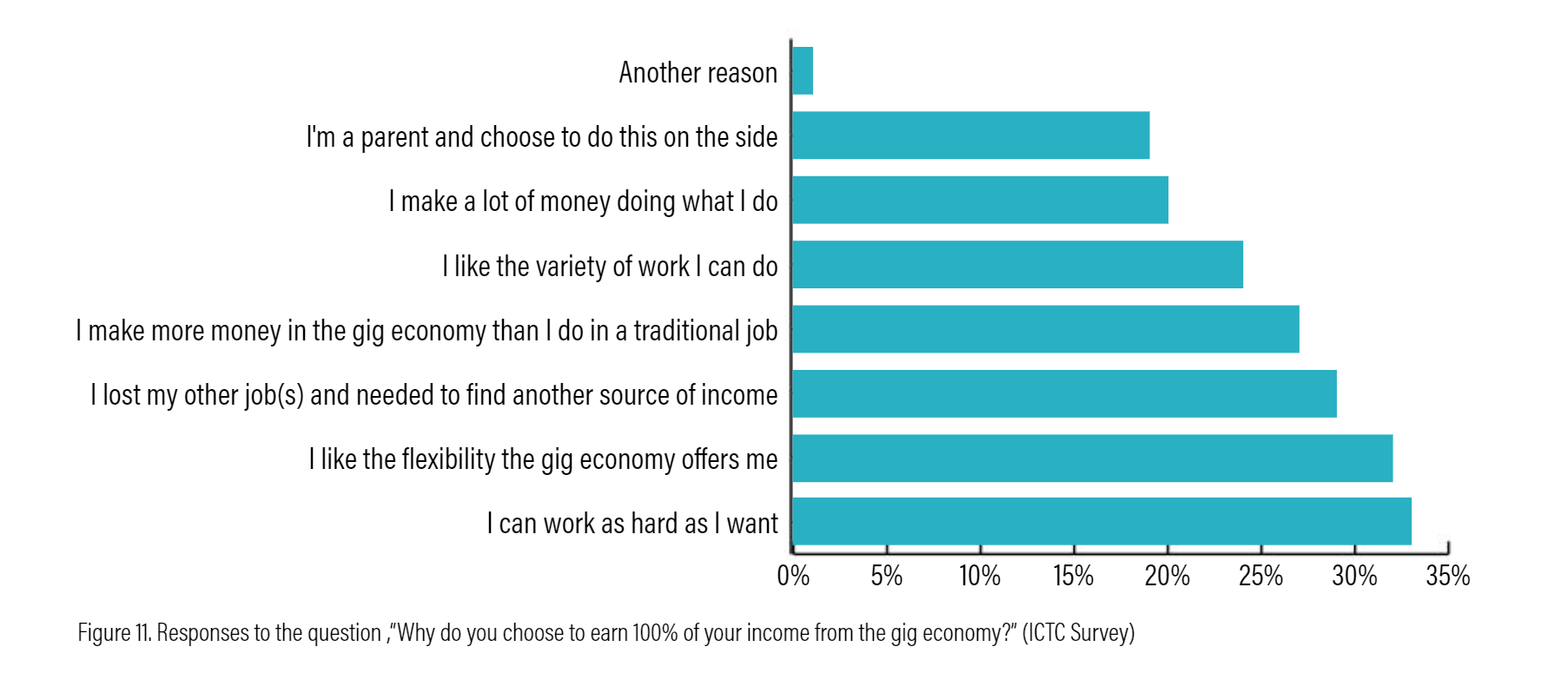

Attitudes and reasons for participation in the gig economy vary based on whether a worker earns all or part of their income in the gig economy.

- Those who supplement their income with gig work are unlikely to transition to full-time gig work (only 13% said they would like full-time gig work)

- Those who earn income exclusively from the gig economy believe their employers take health and safety seriously, have a stable income, and feel supported by their employer

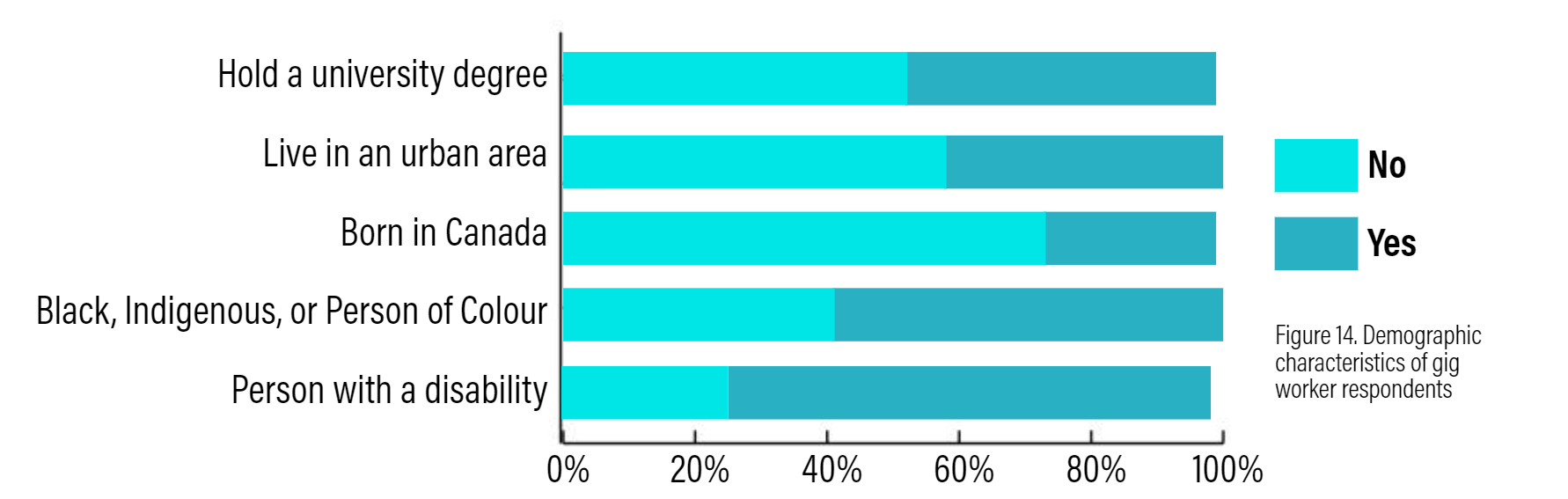

Diversity Among Gig Workers

Gig workers represent a heterogenous population.

Labour and Industrial Relations

Earn money in the gig economy has pros and cons, as does traditional forms of work.:

- A Canadian survey found nearly one in three respondents “can’t make ends meet without [gig] work”

- Survey results also indicate gig workers generally feel they have agency at work

- ICTC’s survey found 78% say they “are their own boss” and have access to fair settlement of disputes (75%)

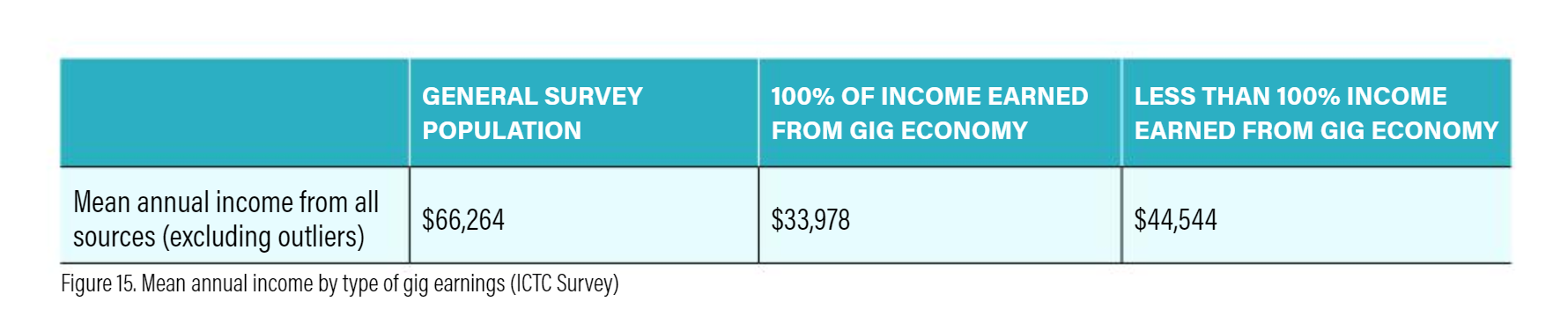

Gig Work Income

Gig work is still described as an atypical form of work — often a part-time and complimentary, rather than a full-time engagement:

- According to Statistics Canada, “earnings of the majority of [gig workers] did not exceed $5000 per year.”

- According to ICTC’s survey, 58% of gig workers earned less than $20,000 per year in the gig economy, with a mean annual gig economy income of $9,667

The Role of Gig Platforms

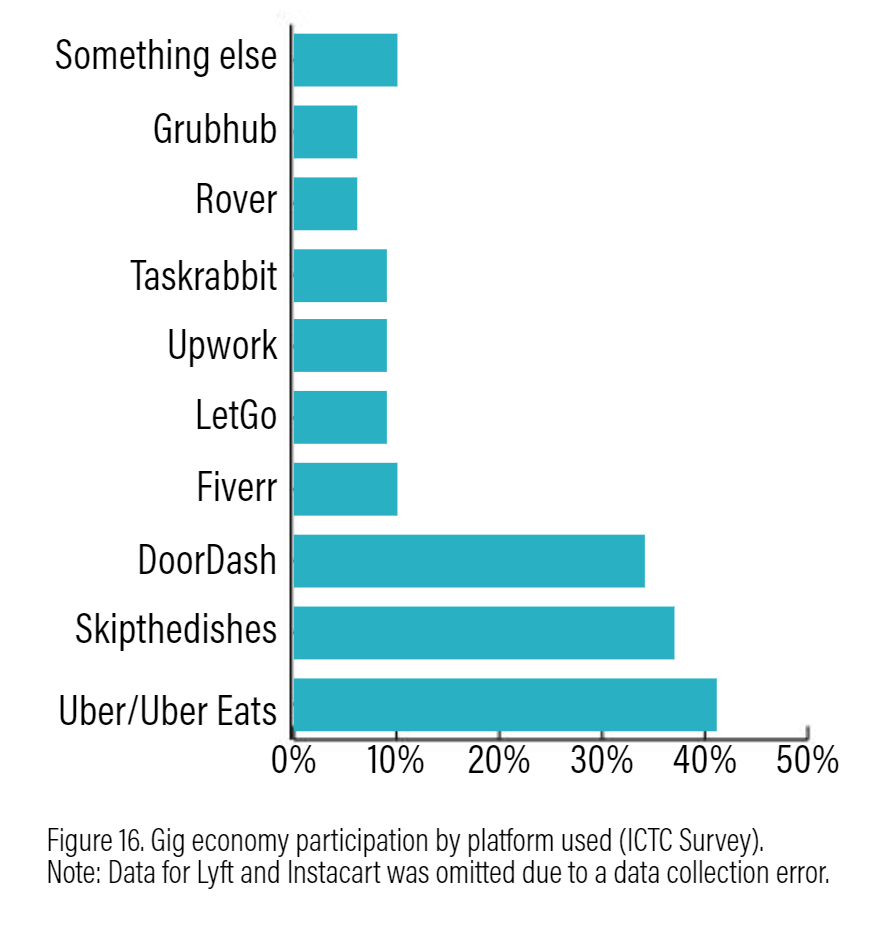

Gig economy growth has been rapid, and 69% of gig workers said they worked in the gig economy for only two years or less.

Many gig platforms operating in Canada are foreign-owned, and only a few Canadian-owned gig companies exist, notably SkipTheDishes, DriveHER, and AskForTask.

Survey responses suggest that the largest Canadian gig economy employers consist mostly of delivery and driving companies:

Regulating the Gig Economy: Beyond the Policy Vacuum

The gig economy is at an inflection point, and government policy that helps to shape the gig economy is urgently needed, with a specific focus on issues of data measurement, taxation, social security, and industry regulation.

To make informed decisions on gig economy policy, data about gig workers must be reliable and gathered regularly. Governments around the world are beginning to respond to gathered data on gig workers and their work conditions:

- The UK’s Taylor Report (built on a national survey of modern work) resulted in a series of recommendations for the government to develop legislation, guidance, and tests to determine employee status as employee or dependent contractor

- In France, Uber drivers have been classified as employees, which could require companies to pay additional taxes, benefits, and paid holidays

Nonetheless, an EU report suggests that “very few countries have taken legislative measures to address the labour and social protection of (self-employed) platform workers.”

The Future of Work

Past predictions for remote work and gig work have often overestimated their impact, and it is uncertain which COVID-era workplace changes will endure.

But as non-standard forms of work continue to grow, the following considerations could help guide an effective, inclusive, and productive future of work.

- Workers, employers, and government should continue to dialogue about improving nonstandard working arrangements

- Internet connectivity that does not limit access to quality employment should follow the proposed roll-out of the Universal Broadband Fund

- Existing employment supports such as EI and benefits need to be accessible to all workers

- Common definitions and measurements of non-standard work are needed for accurate data collection across provinces (for accurate comparisons and trend analysis)

- Tax codes and collections systems will need to be up to date and function effectively across all forms of work

- Effective policies are needed for mental health, the “right to disconnect,” and remote working standards

This article summarizes findings from a full-length study. Read the full report here.