Effective species conservation requires data. High-risk species, however, are often the least surveyed. A new study detailing the devastating impact of white-nose syndrome (WNS) aims to disrupt this paradox. The study represents the most comprehensive dataset on hibernating bat species to date. Researchers found that, in under a decade, white-nose syndrome (WNS) killed more than 90% of little brown, northern long-eared, and tri-coloured bat populations in parts of Canada and the United States. Big brown bat and Indiana bat populations also saw moderate to serious declines. Data for this study was collected using high-tech and low-tech interventions, including roost counts and mobile acoustic surveys.

These surveying technologies and data-driven collaborations continue to improve conservation efforts. Indeed, the use of sensors and AI-assisted sound identification tools for bat management is becoming more common place. While technology has a role to play in conservation science, time-tested low-tech interventions including bat-boxes are often equally, if not more, effective. The loss of bat life due to WNS make these questions about the role of technology in biodiversity management a pressing issue.

Common Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) by JP (CC BY 2.0)

The Information and Communications Technology Council (ICTC) recently spoke with James Watson as part of ICTC’s new Green Tech Series, to help us unravel these questions. James is the full-time Director of Sales and Marketing at Semios Technologies and part-time bat conservation leader, based in British Columbia. Maya Watson, Research and Policy Analyst with ICTC, interviewed James about his conservation work with North and West Vancouver municipalities to create and conserve habitats for bats. In this interview, James and Maya discuss the primary threats to Canadian bat populations and delve into low-tech and high-tech interventions to conserve bats.

Maya: You have diverse work experience including AgTech marketing and working with municipal governments, but I’m wondering what sparked your interest in bats?

James: I’m a lunatic naturalist at heart. I’ve always been fascinated by the natural world, whether it’s entomology, ornithology or mammalogy, so I’ve always appreciated bats. When you think about their evolutionary capacities it’s incredible: bats are the only mammal that can fly and use echolocation for their hunting at the same time!

I read about WNS and the outbreak in 2006, because you’d see these news articles of somebody filming bats flying around in the snow in eastern North America and thought, OK, that’s not good. At the time, I didn’t really appreciating the extent to which WNS would have an impact.

Maya: Could you describe how WNS affects bats in more detail?

James: It’s absolutely shocking the effect it’s had. Little brown bats in some areas of both Canada and the United States [have seen] declines of greater than 95% of the population. WNS is really just an irritant, right? It’s a fungus that grows on their wings, on their nose. It irritates them and wakes them up multiple times during their hibernation. Every time they wake up, it’s an energy sap. They’ve got to reboot their metabolism. That takes a lot of energy. Then they’re active and they don’t have hydration or nutrition. And so, if this happens multiple times, you essentially have bats that starve or dehydrate to death before hibernation season is done. You can imagine the caves where these animals go to over winter. Where there could have been many thousands to tens of thousands, if you have 90 percent plus mortality, imagine what the floor of those caves looks like — just devastating. They suggest that with some of these populations, it could take a thousand years for them to recover. Some may never recover.

Maya: Other than WNS, what are the primary threats to bat populations in Canada right now?

James: WNS is by far the greatest threat compounded by habitat loss. Habitat loss means, in this case, the dependency bats have developed on humans. It’s a coevolution thing. They’ve learned that some of the best places for them to raise their young are in anthropogenic structures. So, attics unintentionally turned out to be beautiful bat homes. Nice, warm, and humid, yet dry — these are great places to raise their young. But, as we’re building new structures, a couple of things happen. I like to think of my old neighbourhood because there’s a phenomenon here not dissimilar to elsewhere in the country. Every old 50-year-old house on a lot with mature trees is getting torn down. All the trees are getting cut down and we’re putting up houses that are two to three times the size and hermetically sealed. So, habitat loss means that any place that [bats] might have lived before their winter hibernation is gone. Now they’ve got to find an alternative. There are less and less of those suitable structures available. At the same time, the need for these habitats grows because of the pressure from WNS. That’s what got me. I decided I was going to be a part of solving the problem for myself and my community.

Maya: You’re currently working with North and West Vancouver municipalities to support bat conservation. How did you get started and what does that work entail?

James: I first visually identified suitable habitat for bats on the North Shore. Then I returned to conduct acoustic surveys since, at times, it’s far easier to hear them than see them. Once I confirmed activity at those spots, then it was, OK, who can I work with to try and do something here? So, I emailed a local volunteer group and explained what I was hoping to do. They made a couple of key connections for me right away and it was great because these individuals at the municipalities were super receptive.

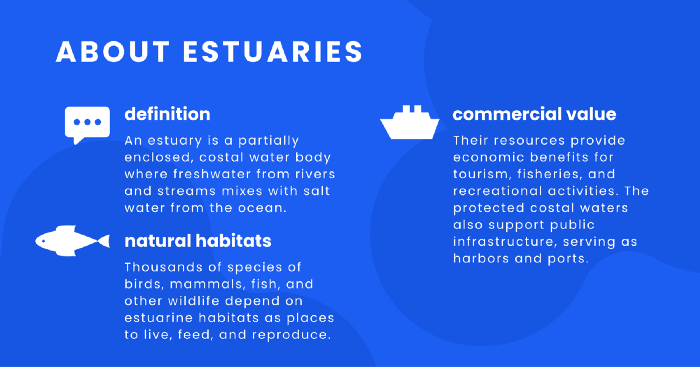

The first site that we did is cool. I don’t know if you know much about estuaries, but they’re the among the most productive and simultaneously threatened habitat on the planet. They’re also the locations where humans have gathered and built our cities and industry. As such, we have tended to fill them in. So, there was a small project to try and restore one in North Vancouver. And, it was coincidentally one of the sites I thought was a good place to install a bat box. That was the first project we completed. It was put up too late in the season, August, to be productive in year one. But, by the following June, we had our first bats taking up residence. And then, by the end of last summer, it was it was pretty busy. It was really inspirational. That got me going, of course.

Source: EPA, 2021

Maya: That combination of acoustic recorders and the traditional bat-box building is an interesting mix of high-tech and low-tech solutions. What other ways can technology help to conserve bats?

James: If you think of an attic, [bats] can move around in the attic to find the right temperature. Bat houses, they’re small. If it gets too hot, they’ve got nowhere to go because bats also don’t like to fly during the day. Bats’ ability to move within the structure to get the right temperature range is important because they can become very stressed or die if they overheat. Actually, one of the big bat colonies in another municipality had about seventy-five bats drop dead out of their bat house three summers ago, most certainly because it got too hot.

So, further to the tech theme: there’s lots of research going on about how to build the perfect box. I happened upon this British Columbia scientist who works with Wildlife Conservation Canada. She did a presentation on the importance of microclimates in [bat] housing structures. They put temperature sensors in the bat roost to understand what happens from a climate standpoint, especially with the advent of climate change. I did a complete re-design for the first project after seeing her presentation. I came up with the idea of two boxes back-to-back and connecting them with an attic. If I’m a bat, now I can move. Not only can I move up and down inside the bat house, I can cross over from one side to the other to find that right temperature gradient. Apparently, a local scientist with the BC Bat Society has applied for funding to put a temperature sensor in one of the boxes I put up to evaluate the internal climate with this different configuration.

Maya: Congratulations! I’ve heard about using AI for bat conservation and I know you use high-tech interventions for pest control management at Semios. Why aren’t these complex technologies more commonplace in bat conservation efforts?

James: You’ve got to remember that this is a human problem. Everybody will tell you nature is awesome. It’s fascinating as long as it doesn’t inconvenience me or cost me money. What we’re doing at Semios is a business. There’s an economic return. But, we don’t assign any economic value to bats. That’s why we end up in these scenarios with the natural world every time. A significant portion of the population is completely unaware or disconnected from nature. And others can’t draw any conclusion that it makes any difference in their daily life. It’s a big challenge for conservationists.

Maya: I’m a birder and I know how helpful data collected by the general population can be to track changes in migration patterns, etc. Is citizen science leveraged in similar ways in the bat conservation community?

James: Technology has spurred so many great tools to enable citizen science. It’s super cool. So, for example, I have an attachable device for my iPhone which takes the ultrasonic acoustic emanations from bats and puts them in a frequency I can hear. There is a lot of noise going on that none of us are aware of when [the bats are] out there doing their thing.

You can also think of applications like iNaturalist or eBird or NestWatch. Those apps have made phenomenal contributions to science in terms of understanding populations, distribution, and health. All these technologies enable some percentage of our population to be more aware and to contribute to measuring what’s happening versus just anecdotal observations. In British Columbia, the goal is to engage citizen science to increase the bat population database, which could help us determine the baseline bat population before WNS gets here. Now the most important question is: what do the Eastern populations that we know of look like today? Is there a remnant group with some residual resistance to WNS that hopefully gets passed on to future generations so that we can start to rebuild the population? I haven’t seen enough of the data on survival yet, but I understand there is a researcher at Trent University doing some work on this.

When it comes to understanding scenarios like this, small datasets aren’t helpful. With enough information, you start to be able to trust it and make sense of it. The more people you enable with these kinds of tools, the better it is for any researcher.

For more information on bat initiatives and places to donate check out the following links:

Canada: https://batwatch.ca/; Bat Conservation Guide

Western Canada: https://wcsbats.ca/Our-work-to-save-bats/Batbox-Project/BatBox-Project-Canada-wide

British Columbia: https://bcbats.ca/

New Brunswick: https://www.nbm-mnb.ca/new-brunswick-museum-wants-to-hear-about-your-bats/

Nova Scotia: http://www.batconservation.ca/

Alberta: https://www.albertabats.ca/